Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

|

With the passage of the Telecommunications and Other Legislation Amendment (Assistance and Access) Act 2018 (Cth) (the Act) well behind it, the Australian Government joined its other partners in the ‘Five Eyes’ or ‘Five Countries’ security alliance — Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US — for a two-day ministerial meeting in London this week to discuss ‘emerging threats’. The types of potential threats under discussion included the increased use and deployment of encryption and other technologies by technology providers, a discussion with echoes of the intense debates that accompanied the Act’s passage last year. This sustained focus on encryption and emerging technologies makes it clear that the Act, which is currently under review, is not the end of the road for the encryption debate. |

The Act was introduced last year to allow law enforcement and intelligence agencies to issue specific requests and notices to certain communications providers, enabling them to access information that could allow them to prevent serious criminal conduct. The Five Countries initially suggested the use of such legislation in a statement released in 2018 (which itself reflected a global conversation that had by then been ongoing for years, if not decades), encouraging governments to “pursue technological, enforcement, legislative or other measures to achieve lawful access solutions” when faced with barriers to access information that could prevent serious criminal conduct and thereby help to protect citizens.

In this more recent round of London meetings, the Five Countries reinforced the need for technology companies to assist law enforcement agencies to access information, including encrypted material, that could help prevent serious criminal conduct, as part of roundtable discussions that have sparked renewed discussion about the Act. In the communiqué ultimately published on 31 July 2019 following the meetings, Ministers from the Five Countries (including Australia’s Home Affairs Minister, Peter Dutton) focused on the issue of online child sexual exploitation and abuse, and the “impacts to the safety of children”, when reinforcing the need for “all sectors of the digital industry including Internet Service Providers and device manufacturers” to reflect on how they develop their systems and services,1 and how they deploy encryption. Despite this narrow framing of the issue, it is clear that encryption remains front of mind for the alliance and further legislative or regulatory action in the Five Countries may follow.

Despite the Five Countries’ support of a legislative regime that achieves this goal, the Act’s introduction in Australia was not without controversy. Late last year we published an article that outlined the Act’s history, and analysed why the Act’s introduction was so contentious. Now, eight months after the Act’s commencement, and following on from the Five Countries’ renewed statement of its strong support of such legislation, we provide a status update on the Act’s implementation, and highlight key outstanding issues.

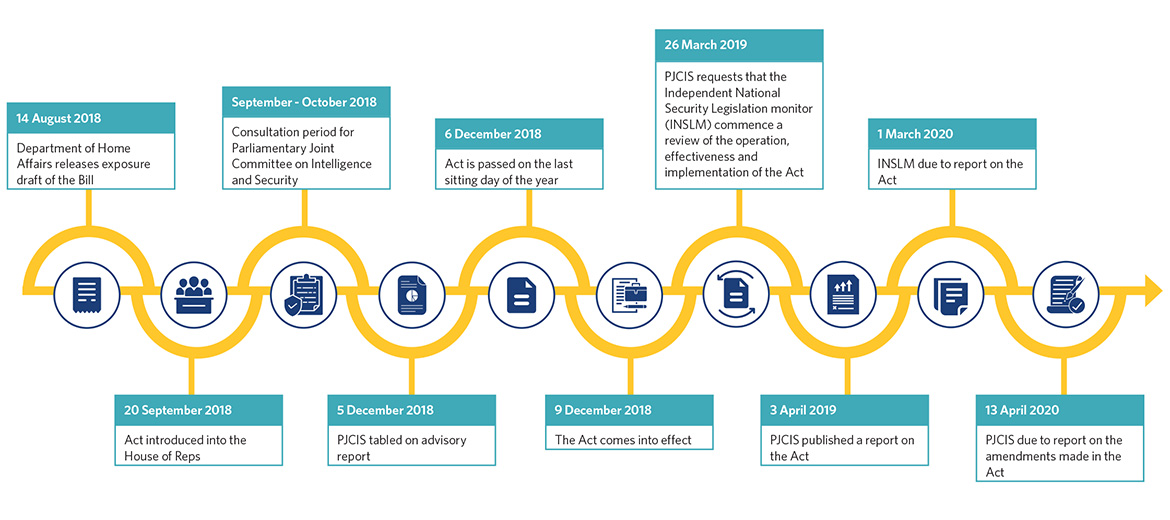

Following a short consultation period, the Act was passed on the final sitting day of Parliament last year in response to stated increased security risks over the holiday period. The passage of the Act was premised on a further review of the Act by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (PJCIS) in the new year (following on from the interim report it published prior to the passage of the Act on 5 December 2018).

The PJCIS later published a report on 3 April 2019 about the Act. In that most recent April report, the PJCIS declined to make any substantial amendments to the Act. However, it did recommend that:

The INSLM review recommended by the PJCIS will primarily focus on whether the Act:

The INSLM is due to report on its findings on 1 March 2020.

A graphic outlining the overall timeline of the Act, both before and after its passage, is set out above.

Prior to the federal election, many stakeholders expected the Act to be amended fairly early in the second half of the year, given the amendments that were proposed by Labor in the Senate on the day of the Act’s passage and abandoned in favour of swiftly passing the Act before the end of 2018. These amendments, and a promised analysis of the economic impact of the Act, now seem less likely to be pursued.

In addition, the Five Countries’ commentary on encryption suggest that developments on related legislative instruments in other jurisdictions are likely to follow (for example, the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 in the UK and the Stored Communications Act and US CLOUD Act in the US), and may also inform the PJCIS and INSLM reviews. It is also possible that the Act could operate as a “stalking horse” for the other Five Countries’ own legislative solutions to the “going dark” problem caused by law enforcement’s inability to access data due to the widespread adoption of technologies such as encryption.3

Closer to home, the PJCIS is also currently reviewing the mandatory data retention regime set out in Part 5-1A of the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 (Cth), which require carriers, carriage service providers and internet service providers to “retain a defined set of telecommunications data for two years”.4 This regime was expanded in 2015 to similarly ensure that data is available for law enforcement and national security investigations.”5 This regime, although applying to a narrower set of technology providers than the Act, touches on similar issues of access to data and also remains the subject of some controversy.

In light of this activity both in Australia and abroad, it will be critical to continue to monitor the Act and related regulation. Providers that are captured by the Act need to be ready to respond to requests and notices, and should be aware that:

In addition, many key issues that were raised both before and after the passage of the Act remain live issues for many stakeholders, and will continue to be brought to the attention of relevant oversight and review bodies.

Some of these issues are outlined above.

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2025

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs