Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

The transition period under the Withdrawal Agreement has now come to an end and, following the last minute announcement of a deal between the UK and EU on 30 December 2020, businesses across the world are assessing the practical implications of Brexit for doing business in the UK and the EU going forward.

But what does the Brexit deal mean for cross-border dispute resolution? What is the impact on English court jurisdiction clauses and on London-seated arbitration clauses? Below we give some answers to the questions that our clients have been asking over the past days and weeks.

In contrast to the Withdrawal Agreement, the Agreement reached between the UK and the EU does not cover civil judicial co-operation between the UK and the EU member states. This particular issue was always going to be resolved outside the formal trade agreement, but has not yet been so resolved. Significant issues remain as set out in this article. The hope is that the fact that agreement was reached will pave the way for a further agreement on judicial cooperation shortly.

Key Terms and AgreementsApplicable law: Applicable law (also called the governing law or substantive law) is the law that governs parties’ rights and obligations under contracts or for tortious acts. Most of our clients will expressly provide for a law to govern their contracts or non-contractual obligations, but in the event that they do not do so, most countries have rules to work out what law should apply. In the EU, these rules are set out in the Rome I and Rome II Regulations. Civil judicial co-operation: Co-operation between countries to clarify which national courts have jurisdiction to resolve cross-border civil and commercial disputes and to ensure that judgments given in those disputes can be enforced in different countries. The Hague Convention: The 2005 Hague Convention on Choice of Court Agreements is an international treaty. Parties to the convention recognise and uphold the jurisdiction of a court which has been chosen in a contractual exclusive jurisdiction clause and will recognise and enforce the resulting judgment. States party are currently the EU, Mexico, Montenegro, the UK and Singapore. The Lugano Convention: The 2007 Lugano Convention is an international treaty between the EU and three European Free Trade Association (EFTA) states, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland. It covers civil judicial co-operation between the EU member states and those three states. The Lugano Convention is substantially the same as the Brussels Regulation before it was “recast”. The New York Convention: This is the name commonly used for the 1958 Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards. This treaty requires the courts of contracting states to uphold agreements to arbitrate and recognise and enforce arbitral awards made in the territory of other contracting states (subject to very limited exceptions). There are over 160 contracting states, including all EU member states and the UK. The Recast Brussels Regulation: The Brussels Regulation 2001 provided a set of rules regulating which courts within the EU will have jurisdiction to hear civil or commercial disputes and providing for mutual recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments. The Brussels Regulation was revised (“recast”) with effect from 2015 with various improvements and the abolition of some formalities. The UK-EU Trade and Co-operation Agreement (the Agreement): a trade agreement signed on 30 December 2020, between the European Union and the United Kingdom. It has been applied provisionally since 1 January 2021, when the transition period ended. The Withdrawal Agreement: Signed on 24 January 2020, this treaty set the terms of withdrawal of the UK from the EU on 31 January 2020 and also contained a transition period (to 31 December 2020), together with an outline of the future relationship. |

The UK officially left the EU on 31 January 2020. However, during the transition period established by the Withdrawal Agreement, EU law continued to apply to, and in, the UK, and the UK continued to be treated by the EU as an EU member state for the purposes of international agreements to which the EU is a party. This meant that the Recast Brussels Regulation continued to apply between the EU member states and the UK. It also meant that the UK continued to be treated by the EU member states (and EFTA states where applicable) as a party to the Lugano Convention and the Hague Convention. Each of these instruments has slightly different provisions, but the important takeaway was that where any of these instruments applied, the UK and EU member states would enforce each other’s judgments and would uphold a contractual exclusive jurisdiction clause in favour of each other’s courts, subject to only very limited exceptions.

The Withdrawal Agreement also allowed for the application of other internal EU rules on choice of applicable law and the service of proceedings, maintaining the status quo.

Under the Withdrawal Agreement, the provisions of the recast Brussels Regulation will still apply to claims that were commenced prior to 31 December 2020. However, the position is different for claims commenced in the UK or an EU member state after this date.

The Recast Brussels Regulation no longer applies between the EU member states and the UK, and the UK is no longer treated by the EU as an EU member state for the purpose of its international agreements.

The UK re-acceded to the Hague Convention in its own right, having previously been party to it via EU membership, with such accession taking effect on 1 January 2021. The Hague Convention therefore remains in force between the UK (now as a separate party) and the EU member states. There is, however, some uncertainty as to whether the EU member states will treat the Convention as having been in force for the UK since 1 October 2015 (when it came into force for the EU member states, at that time including the UK) or from 1 January 2021 (when the UK re-acceded in its own right). The European Commission has so far indicated that it takes the latter view, while the UK the former. This means that where an exclusive jurisdiction clause was agreed before 1 January 2021 (and on or after 1 October 2015), there is some uncertainty as to whether EU member states will treat the clause as falling within the Hague Convention. This is often referred to as the “change of status” risk.

Last year, the UK applied to re-accede to the Lugano Convention with effect from 1 January 2021. However, this requires the unanimous agreement of all the contracting parties. While Iceland, Norway and Switzerland have indicated their support for the UK’s accession, the EU’s position is not yet clear. We expect to have some clarity on this by April 2021.1

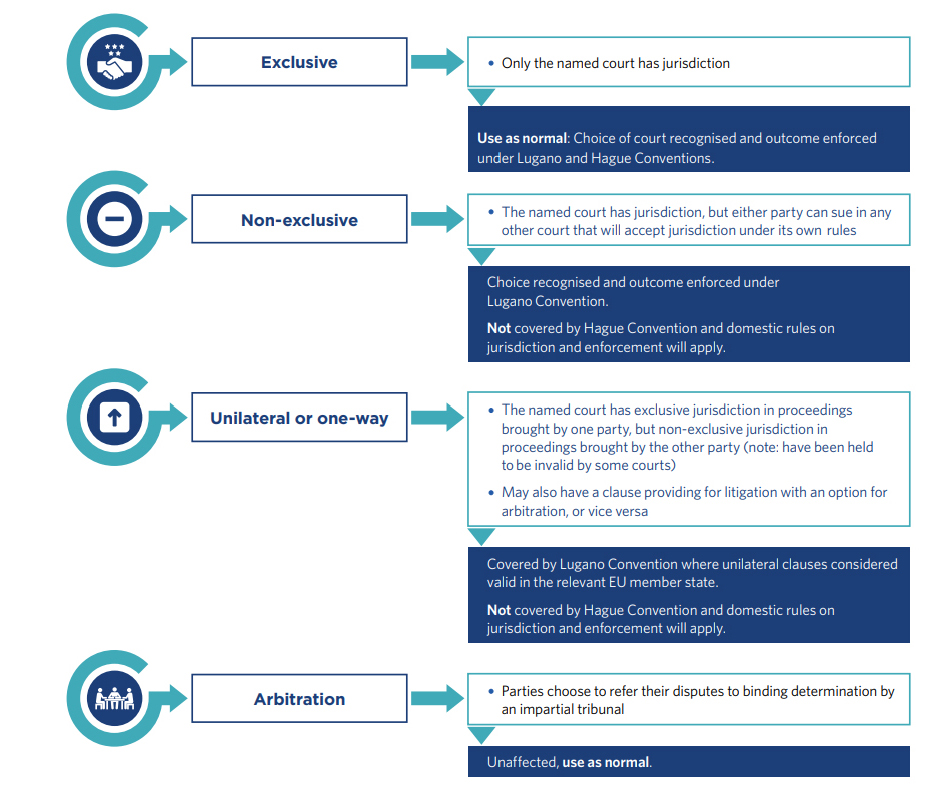

For exclusive English jurisdiction clauses agreed on or after 1 January 2021, the position should be straightforward. EU member state courts will generally respect exclusive English jurisdiction clauses and enforce the resulting judgments under the Hague Convention (as will the other contracting states to the Hague Convention). Where the Hague Convention does not apply (either because of the change of status risk, or because there is a jurisdiction clause which is non-exclusive or unilateral, or which was agreed before 1 October 2015, or simply because there is no jurisdiction clause), the UK and EU member state courts will apply their own rules to questions of jurisdiction and enforcement of judgments.2

Where an EU member state court has jurisdiction under the Recast Brussels Regulation, there is some uncertainty as to the circumstances in which it can stay proceedings or decline jurisdiction in favour of non-EU courts (now including the UK) except where those proceedings are commenced first. Where the non-EU proceedings are first in time, there is an express power to stay proceedings under Articles 33/34 of the Recast Brussels Regulation, but otherwise the Regulation is silent as to any power to stay.

Most EU member states are likely to enforce foreign judgments even without a specific reciprocal regime, although the type of judgment enforced may be more limited and the procedures may be more cumbersome and more expensive.

There will also be a number of other changes: for example, the English court’s permission will be needed to serve out of the jurisdiction in more cases. However, the English court would also be able to issue anti-suit injunctions in respect of proceedings in EU member state courts in appropriate circumstances, such as where an action has been brought in breach of an exclusive English jurisdiction clause.

The Lugano Convention will then apply as between the UK and the EU member states and the three EFTA states while the Hague Convention applies between the UK and the other Hague Convention contracting states. This would mean that very little would change from the pre-Brexit regime in relation to jurisdiction and enforcement of judgments (albeit that the Lugano Convention does not include some of the improvements made when the Brussels Regulation was “recast”). English court judgments would continue to be readily enforceable throughout the EU and in EFTA countries, and English jurisdiction clauses would largely continue to be respected by those countries, and vice versa. Importantly, the Lugano Convention is not limited to exclusive jurisdiction clauses, so there is more scope for parties confidently to use other types of dispute resolution clause without increasing risk. However, potential claimants should be aware that Lugano will only apply to proceedings commenced once the UK has re-acceded,3 when considering the timing of new claims.

In short, no. Arbitration has very intentionally been kept outside the reach of EU law, and because it sits outside EU law, it also means that the whole system of arbitration is unaffected by Brexit.

The agreement to arbitrate is a contractual one, and the interpretation and recognition of that agreement will be a question of each country’s national law (of which there is quite a degree of consistency based on the UNCITRAL Model law) and the New York Convention (to which all EU member states are party). The arbitral process will be governed by the law of the seat of arbitration, alongside party agreement (including institutional arbitral rules where the parties have agreed to apply them), and the discretion of the tribunal. Challenging an arbitral award will be a matter of national law and is usually possible only on very limited grounds. The enforcement of the arbitral award that results from the arbitral process will be governed by national law and the provisions of the New York Convention. Again, there are very limited grounds to refuse enforcement of that award.

So, while Brexit may have a significant impact on many areas of business, it does not have an impact on arbitration as a form of dispute resolution. This makes arbitration a good choice to ensure that the parties’ agreement as to forum is upheld and the outcome of a dispute resolution process can be enforced. Regardless of Brexit, arbitration can have advantages in a cross-border context over litigation, including ease of enforcement, party autonomy and flexibility, limited grounds to challenge or appeal, neutrality and privacy in the arbitral process.

Yes. English law remains a sensible, commercial choice. English law has long been a popular choice of substantive law in international contracts, many of which have no nexus with England, the parties or the place of contractual performance. English law is chosen due to the well-developed body of English contract law principles. With only a small number of exceptions (such as consumer and employment contracts), English contract law has developed largely independently of the UK’s membership of the EU and is predominantly unaffected by the body of EU law. The question of whether English law remains the right choice of substantive law will therefore be subject to the same considerations as it was before Brexit occurred.

The obvious next question is whether a contractual choice of English law would be upheld by EU member state courts. The answer again, is yes. EU courts will continue to apply the Rome I and Rome II Regulations, and these respect the express choice of the law of an EU member state or a third country law (now including the UK) in the majority of circumstances. As a result, EU member state courts should continue to give effect to a contractual choice of English law. It is also worth noting that the UK has adopted the provisions of Rome I and Rome II into its own legislation and will therefore follow the same approach when it comes to a choice of governing law of an EU member state (or any other country).

Understanding the practical implications of the legal framework can be challenging. The chart below summarises the application of the Hague Convention and re-accession to the Lugano Convention to the standard dispute resolution clauses used in most contracts.

However, the uncertainty around the UK’s re-accession to the Lugano Convention does not mean you should immediately be changing your approach to your dispute resolution clauses. It is important to consider four elements before reaching a conclusion on which dispute resolution clause will be best for you.

First of all, it is really important to remember that this is an EU/EFTA/UK issue and that the position hasn’t changed for the rest of the world. So if you are a UK company and are contracting with a counterparty in the US with assets in the UK and the US, the position remains as it was before and Brexit doesn’t affect your choices.

Similarly, if you may have to enforce a judgment outside the EU, choosing a dispute resolution clause that would be enforced in the EU but would not produce a judgment that can be enforced elsewhere isn’t advisable. For example, choosing an exclusive English court jurisdiction clause because it definitely fits within the Hague Convention is not a sensible choice if you need to enforce the resulting judgment in a jurisdiction where English court judgments are not enforceable. If you are going to need to enforce in multiple jurisdictions across the world (including within the EU) then the balance shifts towards arbitration being the preferred choice.

The governing law of your contract is also an important factor. Generally (but not always) parties will try to ensure that their jurisdiction clause matches the governing law to make sure that the courts are applying their own domestic law (eg English law, English courts). Where that isn’t possible, they may choose arbitration.

Finally, some contracting parties may not be able to identify where disputes may arise or where they may need to enforce a judgment or arbitral award. In those circumstances, flexibility may trump all other factors and including a unilateral option involving arbitration (either as the default or as the option) may be a sensible choice.

Where that analysis leads you to conclude that the right choice is an English court jurisdiction clause and enforcement is likely to be needed in the EU, an exclusive English court jurisdiction clause is likely to be your best choice, at least for the moment. Where other factors come into play, particularly if there are multi-jurisdictional enforcement options or the counter-party is not prepared to agree to exclusive English court jurisdiction, arbitration (English-seated or otherwise) is likely to remain the best option.

While the legal framework for jurisdiction and enforcement of judgments has changed, its significance is undiminished: the choice of dispute resolution mechanism remains a fundamental part of any contract in order to ensure the enforceability of the parties’ obligations.

Footnotes

Partner, Global Co-Head of International Arbitration and of Public International Law, London

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs