Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

Keeping up with arbitration developments in India can be challenging. We take you through the arbitration clauses and what this means for Indian subsidiaries of international businesses

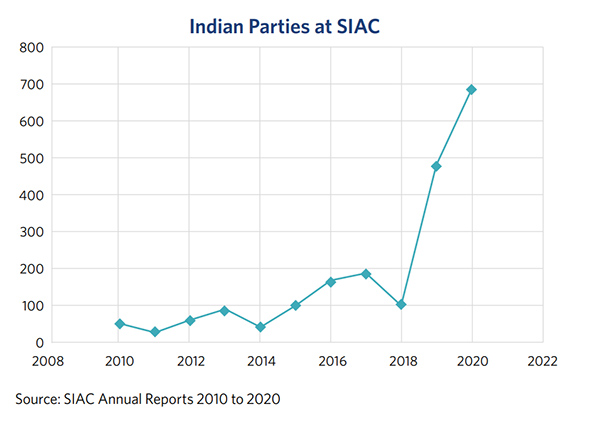

Since 2015, the arbitration law has been amended three times, two major arbitration institutions have been established and the government has proposed a quasi-regulator for arbitrators and arbitral institutions. Yet one development that stands out is a judgment from the Supreme Court of India in April 2021 in PASL Wind Solutions v. GE Power Conversion India that allows two Indian parties to resolve disputes by arbitration outside of India.

The judgment is significant to Indian subsidiaries of international businesses who now have greater freedom in their choice of dispute resolution options for commercial contracts. Equally, Indian companies doing business internationally will likely welcome the flexibility to resolve their disputes in popular jurisdictions like Singapore, London and New York (to name but a few). In either case, the judgment is an opportunity for businesses to refresh their approach to dispute resolution clauses in India-related commercial contracts. This article explains the background to the judgment, what it means for arbitration clauses and the challenges that remain.

Arbitration in India is governed by the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (Arbitration Act). The Arbitration Act differentiates between arbitrations with their 'seat' or 'legal place' in India and those with their seat outside India. The choice of seat often determines which country's arbitration law applies and which courts have supervisory jurisdiction over the arbitration. Under Indian law: (i) two non-Indian parties or (ii) an Indian party and a non-Indian party can choose to arbitrate their dispute offshore, that is, to choose a seat other than India. However, there were conflicting judgments on whether Indian parties to a contract could choose an offshore seat. Some High Courts had held that an award arising out of such an arbitration could not be enforced, while others reached the opposite conclusion.

In PASL Wind Solutions Private Limited v. GE Power Conversion India Private Limited (PASL Wind), the Supreme Court of India, the highest appellate court, finally resolved the debate. In this case, two companies incorporated in India (one a subsidiary of a French company) entered into a settlement agreement. The agreement provided for arbitration seated in Zurich under the ICC arbitration rules and was governed by Indian substantive law. The tribunal issued an award and GE Power applied to enforce it in Gujarat. The Gujarat High Court held that the award was enforceable notwithstanding that the two Indian parties had chosen a foreign seat, but also held that parties to such an arbitration would not be entitled to interim relief in the Indian courts. PASL Wind Solutions appealed to the Supreme Court.

The issue before the Supreme Court was whether a foreign award (being an award issued by a tribunal seated outside India) included an award arising out of a dispute between two Indian parties. The appellant argued that the participation of two Indian parties meant that the award did not satisfy the definition of a foreign award. The court rejected this argument and held that there were four criteria for an award to be considered a foreign award:

The court held that these criteria were met by the award in question. It did not matter that the parties were companies incorporated in India.

Another issue before the court was whether an agreement between two Indian parties to arbitrate in a foreign seat was against the provisions of the Indian Contract Act 1872. In particular it was argued that the agreement was against public policy and in restraint of legal proceedings and was therefore void.

On public policy, the court found that, on balance, there was no harm to the public in allowing two Indian parties to resolve their disputes offshore: “The balancing act between freedom of contract and clear and undeniable harm to the public must be resolved in favour of freedom of contract as there is no clear and undeniable harm caused to the public…”. The Court also reaffirmed previous judgments in which it held that party autonomy was “the brooding and guiding spirit of arbitration” and that there were no grounds on which to restrict this autonomy by preventing Indian parties from arbitrating abroad.

Finally, the court also held that the parties could seek interim relief under the Arbitration Act from courts in India.

The choice of seat decides the law that applies to procedural matters but not substantive matters. Can two Indian parties also choose to apply a non-Indian substantive law to their dispute? The Supreme Court considered the issue only briefly in PASL Wind and did not provide a full answer. It observed that even if parties choose a foreign law, conflict of law rules would usually have regard to Indian law where it "prohibits a certain act". It also commented that where a foreign award was contrary to the fundamental public policy of India, it would be a ground to refuse enforcement of an award under the Arbitration Act. Accordingly, it will remain important for parties to consider carefully whether and to what extent Indian law and public policy might affect their contract and the enforcement of their award.

The Arbitration Act provides that even where the seat of arbitration is outside India, the parties are entitled to seek interim relief from courts in India, unless the parties agree otherwise. PASL Wind confirmed that this provision would apply also where two Indian parties agreed to offshore arbitration. When drafting an arbitration clause, it will be important to consider whether (and to what extent) to exclude recourse to the Indian courts.

The New York Convention sets out the process that signatory countries must follow to enforce a foreign award and the grounds on which they may refuse enforcement. However, an application to enforce an award is still subject to the procedural rules of the country in which enforcement is sought. Therefore, even if a dispute is arbitrated offshore, if enforcement in India is necessary the complexities of litigation in the Indian courts (and the delays involved) will still need to be navigated.

Another unfortunate quirk of Arbitration Act is that the courts may only enforce a New York Convention award where the government has issued a notification in the Official Gazette, declaring that the country is a New York Convention country. Therefore, even if the award is issued in a New York Convention state, it is possible that the Indian courts will not enforce it unless the country has also been recognised as a New York Convention country in the Official Gazette.

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2025

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs