Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

Respondents continue to identify Beneficiary Disputes (ie disputes between the trustee and one or more of the beneficiaries) as a significant challenge. However, trustees' primary concerns remain in other areas, with Beneficiary Disputes ranking as the sixth most pressing issue. In this article, we consider how steps taken by the settlor early in the life of the trust may help avoid disputes.

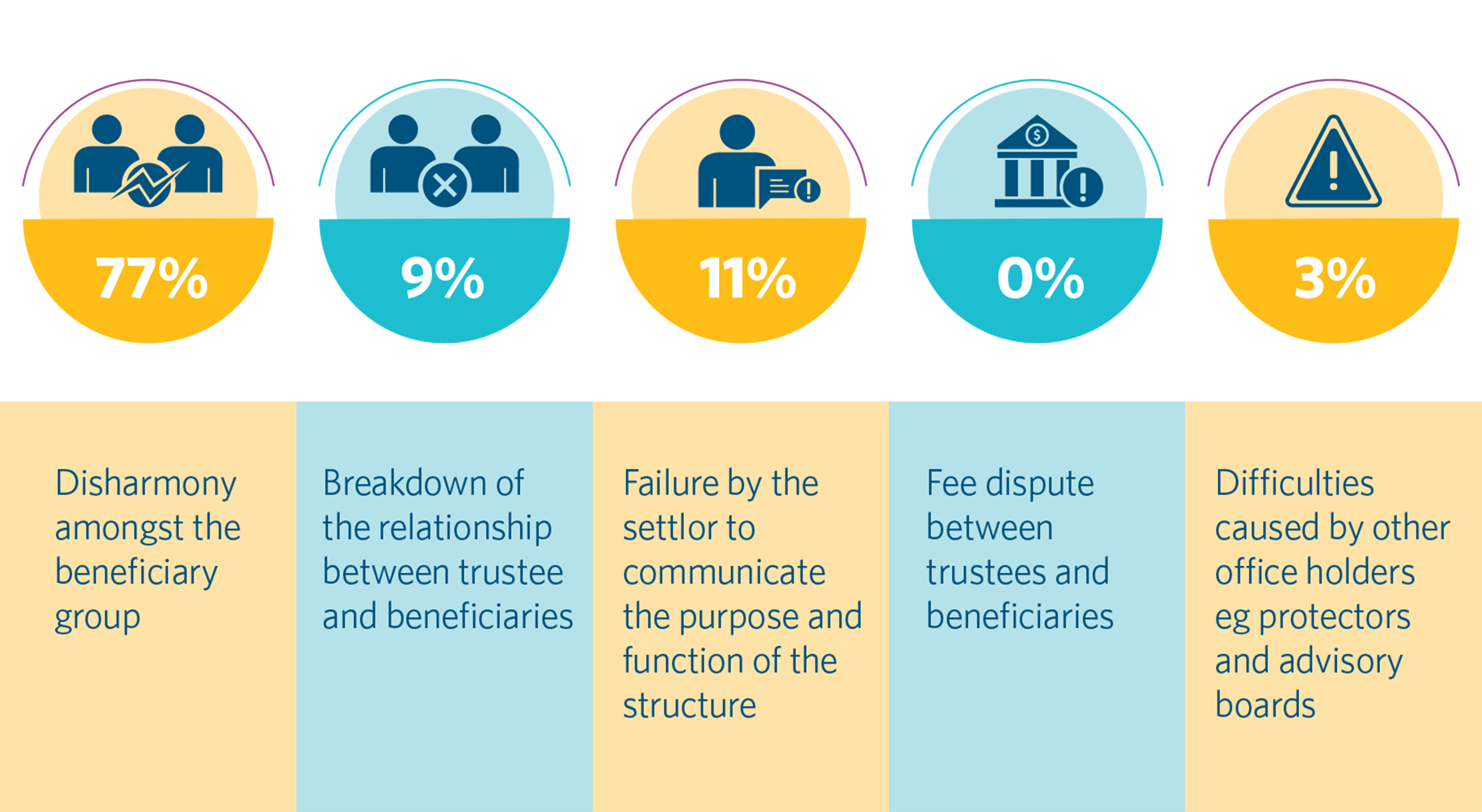

As with the first edition of this survey, we asked respondents to identify the top source of beneficiary disputes. Once again, disharmony between the beneficiary group was head and shoulders above other causes (2022 = 77%; 2020 = 64%). This was followed by: failure by the settlor to communicate the purpose and function of the structure (2022 = 11%; 2020 = 10%); the breakdown of the relationship between the trustee and the beneficiates (2022 = 9%; 2020 = 12%); difficulties caused by other office holders eg protectors and advisory boards (2022 = 3%; 2020 = 4%); and – with a nil return – fee disputes between the trustees and beneficiaries (2022 = 0%; 2020 = 10%).

Given that beneficiary disharmony and settlors' failure to communicate have ranked very highly in both editions of this survey as a cause of beneficiary disputes with trustees, in this article we explore whether the latter may be a key contributing factor to the former. Put another way, might a significant cause of beneficiary disharmony be a failure on the settlor's part to communicate their wishes? And if the disgruntled beneficiaries also act as office holders within the trust structure (see the fourth ranking cause, above), might that make matters worse?

We believe that the answer to both questions is yes, which leads us to discuss steps that may be taken to calm the waters.

It will no doubt be a common feature of many readers' trusts business or practice that beneficiaries fall out. Beneficiaries may perceive a slight if an asset they thought was bound for them ends up in another's hands, or may think they have been treated unfairly if they receive a smaller overall share of the trust fund than other beneficiaries. This, in itself, can cause disharmony amongst the beneficiaries and, ultimately, a dispute with the trustee (particularly so in the context of a discretionary trust, where a beneficiary may find it difficult to accept the trustee's decisions on how assets are distributed).

However, disharmony often increases where the aggrieved party is not only a beneficiary, but also has a role to play in the administration of the trust.

It is not uncommon for trust instruments to provide a degree of power to a party or parties other than the trustee. The label given to this role differs from trust to trust (protector, advisor, appointer, guardian, supervisor or other variation on that theme), and the scope of the role itself is not set in stone. However, a useful working definition for the purposes of this article is someone, other than a trustee and whom we will call a Protector, who occupies an office established by a trust instrument and has powers or rights which allow them to participate in the trust's administration.

These powers and rights can come in various forms. Most relevantly for our purposes, a trustee may have to obtain a Protector's consent to exercise their power to distribute trust funds. There are recent and competing analyses as to how far a Protector can go in withholding this consent,1 but – on the wider view – a Protector may veto a trustee's decision to distribute funds, even if that decision is one which a reasonable body of properly informed trustees could have decided on.2

However, a difficulty may arise where there is more than one Protector from whom the trustees must obtain this consent, and may be magnified where those Protectors are family members who harbour the grievances referred to above.

Take the following example:

It is not difficult to imagine a situation where Children C and D feel aggrieved by their entitlement to 50% less of the trust fund than their half siblings. Nor is it difficult to imagine that, in such circumstances, Children C and D may exercise their veto (on the wider view of consent) to block any distribution which the trustee decides to make to Children A and B (and Children A and B do the same to Children C and D, by way of retaliation). The trust would therefore be deadlocked, with the trustee likely to become embroiled in litigation, not least as to whether the wider or narrower3 view of Protector consent applies to these facts.

It might seem surprising to some, but we have seen trusts which are set up this way – perhaps based on a settlor's misplaced optimism concerning their children.

Equally, there are the scenarios where comparatively little (if anything) is left to family members, but instead the lion's share is to go to charity, and family members are charged with working together to achieve philanthropic aims.

We have a seen a number of cases where the settlor's philanthropic intentions and desires were not universally accepted amongst the beneficiary/protector group.

If Children C and D lived their lives having understood themselves to be held by the settlor in at least as high regard as Children A and B, and in the expectation that they would receive at least 50% of the trust fund upon the settlor's death, then one may be sympathetic to their frustration upon learning after their mother's passing that their entitlement was half what they expected.

We would suggest that these feelings, and the risk of any consequent dispute, could perhaps have been mitigated by better communication between the settlor and her children, and that a professional trustee could have an important part to play in that process, both as someone alive to the best interests of the beneficiaries as a whole, and as someone keen not to become involved in a dispute.

We would also suggest that clear communication by the settlor to the trustee, beneficiaries, and any third party office holders of the trust's purpose and function is – in many cases – best practice. However, we consider that such communication becomes more important where beneficiaries are (or are likely) to receive unequal (or unexpectedly low) distributions (either in a fixed trust or on the basis of the settlor's wishes in a discretionary trust), and more important still where those beneficiaries have the power to disturb the smooth running of the trust or impact its other beneficiaries.

In terms of how such communication could be structured, we believe that, generally, it is preferable:

Of course, such a meeting may be very far outside a settlor's comfort zone, and they may (understandably) be reluctant to expose themselves to the risk of confrontation, or expose others to the risk of upset, by calling the beneficiaries together and saying who is getting what and – perhaps worse – why.

However, we consider this to be an area where value can be added by the trustee. For example, the trustee could explore with the settlor whether, by not grasping the nettle now, the risk of a family dispute in the future is increased. Put another way, if the settlor believes that explaining the operation of the trust would lead to a difficult conversation during her lifetime, does that amount to a tacit acknowledgment that one or more beneficiaries are likely to be upset by her intentions? If the answer is yes, it would seem that early communication may help.

The trustee might be reticent for too much information to be shared, especially in the context of a discretionary trust where it might be regarded as making the trustee's job harder in due course, particularly if they decide to depart from the settlor's wishes. However, the trustee could also offer to help shape the messaging, to see whether the sting of any particularly sensitive issues could be taken out, or at least dulled. Or they could help by acting as a sounding board to consider how a particular message may be received by a beneficiary, and whether that perception chimes with what the trustee is in fact trying to say.

Finally, if the settlor agrees in principle with the value of communication, but is unwilling to deliver the message herself, the trustee could offer to do so. However, the obvious downside in this approach is that it puts the trustee in the middle of potential grievances – and risks alienating beneficiaries – from day 1. That said, the alternative might simply be postponing that outcome to a time when the settlor is not around to provide the trustee with some measure of protection.

Ultimately, whichever form it takes, we do consider communication to be key. In a world where (a) beneficiary disharmony and (b) settlors' failure to communicate continue to be leading causes of trustee involvement in beneficiary disputes, there is much to be gained in improving the latter in the hope of reducing the former. It may also help put the settlor's mind at rest.

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2025

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs