In Enka Insaat ve Sanayi AS v OOO Insurance Co Chubb [2020] EWCA Civ 574, the English Court of Appeal restrained OOO Insurance Co Chubb (“Chubb Russia”) from pursuing Russian court proceedings brought in breach of an arbitration agreement. In this important decision, the Court of Appeal set out how the court of the seat should handle applications for an anti-suit injunction, confirming that forum conveniens questions are irrelevant for this purpose. In addition, the Court of Appeal has sought “to impose some order and clarity” on how the governing law of the arbitration agreement should be determined (the “AA law”) under English law.

Background

Enka Insaat ve Sanayi AS (“Enka”) was a party to a contract under which it was to perform equipment installation works at a power plant (the “Contract”). The Contract contained an arbitration agreement, which provided for disputes to be resolved by London-seated arbitration under the ICC Rules (the “Arbitration Agreement”).

Following a fire at the power plant, Chubb Russia paid out US$400 million in respect of the resulting losses to its insured, the other party to the Contract. Chubb Russia argued that it was subrogated to the claims of the counterparty and sought to recover from Enka in the Russian courts in respect of the sums Chubb Russia had paid out (the “Russian Court Claim”).

Russian court proceedings

Chubb Russia filed the Russian Court Claim in May 2019. However, due to various deficiencies in the Claim, which were not eliminated until September 2019, the substantive hearings took place only in January and February 2020. In March 2020, the judge announced the operative part of the judgment (with the reasoning to follow) dismissing both (i) the Russian Court Claim on the merits; and (ii) Enka’s motion seeking dismissal without considering the merits, in reliance on the Arbitration Agreement.

English court proceedings

As discussed in one of our previous blog posts, Enka made an urgent ex parte application for interim relief to the English Commercial Court, seeking an order requiring the defendants to withdraw the Russian Court Claim, and seeking a stay of the Russian court proceedings. The Court found that the matter was not in a position to proceed, because it was insufficiently prepared to enable there to be a fair hearing. It then determined that there should be an expedited trial commencing in December 2019.

After the trial the Court refused, on forum non conveniens grounds, to grant an anti-suit injunction restraining Chubb from pursuing the Russian Court Claim. The Court also noted that the scope and the governing law of the Arbitration Agreement should be determined by the Russian court. It held, in the alternative, that the anti-suit injunction should be refused due to Enka’s (i) delay in bringing proceedings in the English courts; (ii) degree of participation in the Russian Court Claim; and (iii) failure to commence arbitration proceedings. Enka appealed, arguing, in particular, that the Court’s approach to deciding the case on forum non conveniens grounds was wrong in principle.

The Court of Appeal decision

The Court of Appeal agreed with Enka, allowing the appeal. It concluded that: (i) the English court as the court of the seat was necessarily an appropriate court to grant an anti-suit injunction and questions of forum conveniens did not arise; (ii) the Arbitration Agreement was governed by English law; and (iii) there were no other reasons to refuse relief.

Forum conveniens questions irrelevant

The Court of Appeal explained that forum conveniens questions were irrelevant when a court of the seat decided whether to grant an anti-suit injunction. The choice of the seat is an agreement of the parties to submit to the jurisdiction of the courts of that seat in respect of such powers as the seat confers. The grant of an anti-suit injunction to restrain a (threatened) breach of the arbitration agreement is an exercise of such powers. If a court of the seat were to defer on forum conveniens grounds to the non-curial court, this would defeat the considerations of certainty and party autonomy.

The Court of Appeal further noted that, when faced with the question of whether to grant an anti-suit injunction, the English court must address the following two questions: (i) whether the foreign proceedings are a breach of the arbitration agreement (under the AA law); and (ii) if so, whether relief should be granted as a matter of discretion. Therefore, the Court of Appeal concluded that the Court was wrong not to decide whether the Russian Court Claim was a breach of the Arbitration Agreement.

Governing law of the Arbitration Agreement

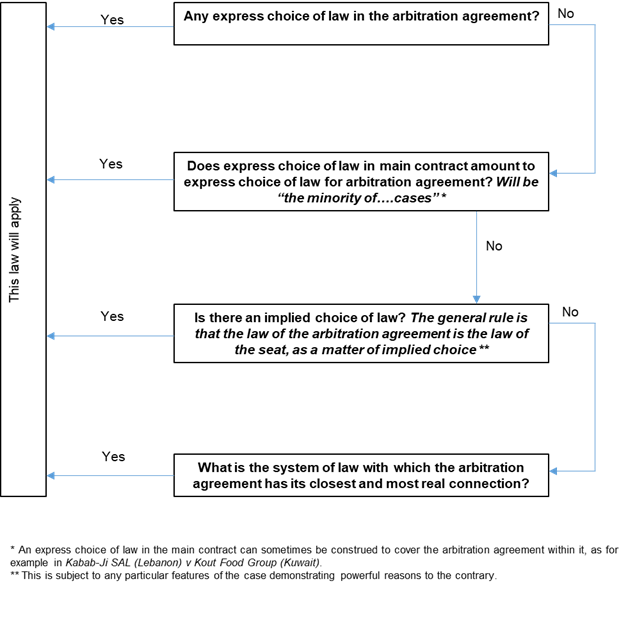

The Court of Appeal noted that “the time [had] come to seek to impose some order and clarity” on the significance of the main contract law and the law of the seat for the purpose of determining the AA law, setting out the following principles:

Applying the above principles, the Court of Appeal concluded that the Arbitration Agreement was governed by English law. The term “Applicable Law” was defined in an attachment to the Contract so as to cover Russian law, with a particular focus on relevant regulatory legislation. The Contract did not have a clause which provided that it was governed by the Applicable Law, but merely provided that the terms used in the Contract would have the definitions set forth in the attachment.

Therefore, there was nothing to suggest an express choice of Russian law as the governing law of the Contract and/or the Arbitration Agreement. Accordingly, in the absence of any countervailing factors which would point to a different system of law, the parties had impliedly chosen that the Arbitration Agreement was governed by the law of the seat, i.e. English law.

The Court of Appeal then noted that the parties to the Contract would expect all aspects of the dispute, whatever their legal basis, to be covered by the Arbitration Agreement, concluding that the Russian Court Claim was brought in breach of the Arbitration Agreement.

No other reasons to refuse relief

According to the Court of Appeal, Enka’s failure to commence arbitration proceedings was not a relevant factor. As confirmed in AES Ust-Kamenogorsk (discussed in one of our previous blog posts) an arbitration agreement contains an independent negative promise not to commence proceedings anywhere in the world. Likewise, Enka’s degree of participation in the Russian Court Claim could not be a matter for legitimate criticism.

The Court of Appeal referred to Ecobank Transnational Inc v Tanoh (discussed in one of our previous blog posts) to confirm that Enka’s delay in bringing proceedings in the English courts could, in principle, justify a refusal to grant relief. However, it concluded that Enka could not be criticised for not seeking relief until it became clear that the Russian Court Claim would be accepted by the Russian courts in September 2019, and Enka sought injunctive relief only 12 days later. As for the Court’s reproach regarding Enka’s handling of the interim application, this did not result in any delay in obtaining injunctive relief. Therefore the Court of Appeal held that there were no other reasons to refuse relief.

Comment

This case has clarified the English law position in relation to the role of the court of the seat when granting anti-suit injunctions. The judgment confirms that forum non conveniens is not a relevant factor to consider when assessing whether anti-suit injunction relief should be granted and illustrates the English courts’ robust approach to breaches of arbitration agreements.

This Court of Appeal decision is also a welcome clarification of how the law of the arbitration agreement should be decided. The case is important in this respect and is likely to become a significant English law authority on the applicable principles. While the case has emphasised the importance of the law of the seat in ascertaining the governing law of the arbitration agreement, the starting point remains a consideration of any express choice of law. In some cases, the choice of law in the main contract will still be considered to be an express choice of law for the arbitration clause itself. The courts will also still assess the legal system with which the arbitration clause has the closest and most real connection. Some uncertainty is therefore likely to remain in relation to how the test will be applied in individual cases. The decision highlights once again the importance of including an express choice of law in the arbitration agreement itself.

For further information, please contact Craig Tevendale, Partner, Rebecca Warder, Professional Support Lawyer, Olga Dementyeva, Associate or your usual Herbert Smith Freehills contact

Key contacts

Disclaimer

The articles published on this website, current at the dates of publication set out above, are for reference purposes only. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action.