The SCC Arbitration Institute was at the forefront of the development of emergency arbitration proceedings, which now constitute a permanent part of the international arbitration landscape. The end of 2019 marked a decade since the arbitral institution's innovative rules amendment. In April this year, the SCC released a report analysing its emergency arbitration statistics, which demonstrate the success of these once novel provisions.

The introduction of emergency arbitration

In January 2010, the SCC introduced into its rules Appendix II, which provided for emergency arbitration. While there were some precursors to emergency arbitration rules (such as the ICC pre-arbitral referee procedure and the ICDR article 37 emergency measures provisions), the emergency arbitration rules implemented by the SCC represented one of the first examples of modern emergency arbitration provisions. Since these rules were promulgated, other leading institutions have followed suit, issuing their own emergency arbitration rules with a variety of refinements, for instance the SIAC, the ICC, the HKIAC and the LCIA.

The emergency arbitration rules allowed parties for the first time to make an application to the SCC for the urgent appointment of an emergency arbitrator who would be empowered to make emergency decisions on interim measures before the case had been referred to the arbitral tribunal. An emergency decision on interim measures was to be made not later than five days from the date when the application was referred to the “Emergency Arbitrator”. The SCC board could extend the five-day time limit upon a reasoned request by the Emergency Arbitrator, or if otherwise deemed necessary.

A decade in review

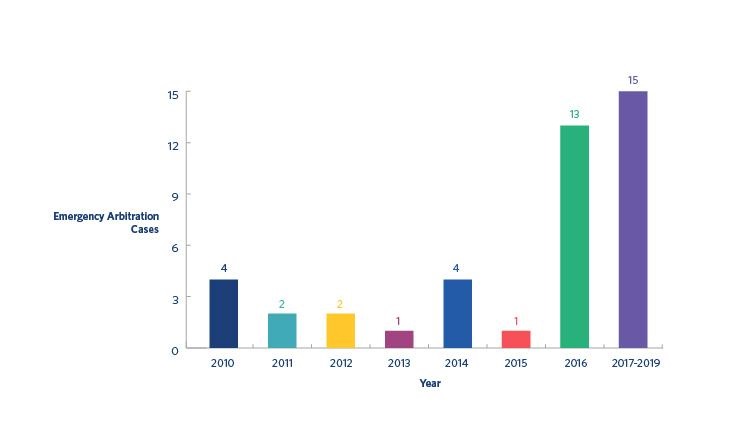

The end of 2019 accordingly marks 10 years since this innovative amendment. In this time, the SCC has received 42 applications for emergency arbitration with the highest number of applications in any year being in 2016 with 13 applications. The individual annual figures for 2017-2019 have not yet been published, however we can deduce from the decade review materials that 15 emergency arbitrations have taken place in total across those three years.

Emergency arbitration cases by year 2010-2019

Across the decade, 2% of the SCC's total cases were emergency arbitration proceedings. However, with the exception of 2016 which had an unusually high number of cases, there is no apparent increasing trend in the use of emergency arbitration.

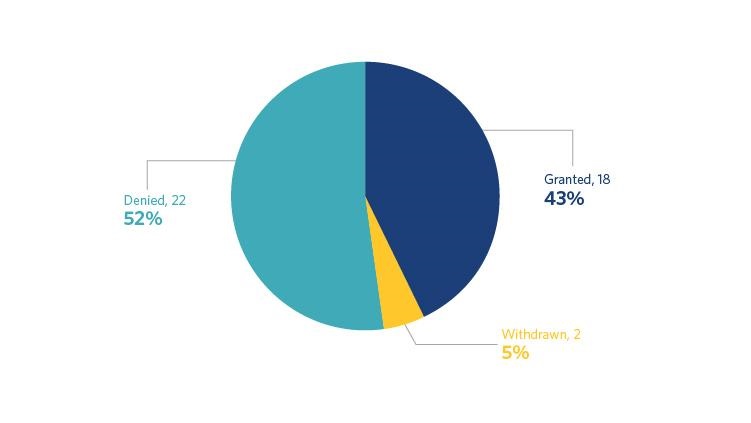

While interim measures are traditionally perceived as being difficult to obtain, the statistics will make pleasant reading for prospective applicants. Over the ten-year period, the statistics reflect relatively balanced prospects of success, with 52% of applications for interim measures being dismissed and 43% being granted. The remaining 5% of applications were withdrawn prior to an award. However, it is difficult to draw any clear conclusions given the small sample size and in the context where applicants with weak prospects are likely to opt out of making interim measures applications altogether.

Outcome of Emergency Arbitration at the SCC 2010-2019

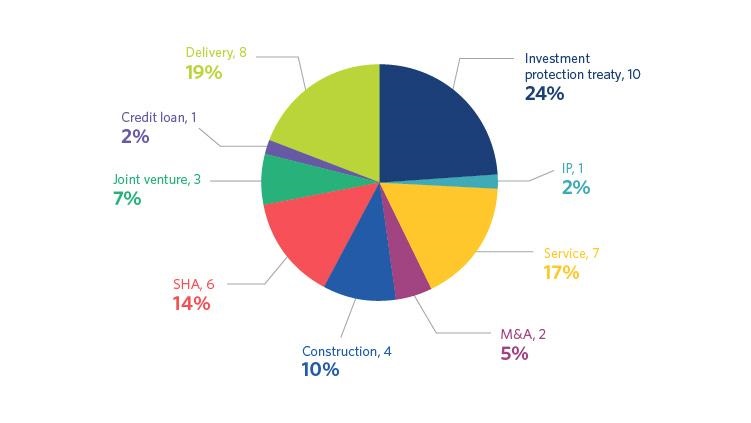

Analysis of the type of dispute demonstrates the breadth of the SCC caseload and the broad use of emergency arbitration. Interestingly, while investment treaty arbitrations only composed 3% of the SCC caseload in 2019, they are over-represented in the historic emergency arbitration caseload, constituting almost one-quarter (24%). This may reflect the prevalence of interim measures applications in investment arbitration more generally. The remaining cases involved a variety of underlying contracts: delivery agreements (19%), service agreements (17%) and shareholders agreements (14%).

Type of Disputed Agreement 2010-2019

Comparison with other institutions

Following the SCC's introduction of emergency arbitration, a number of other institutions quickly followed suit, notably including SIAC, ICC, HKIAC and LCIA. SIAC incorporated emergency arbitration into its 1 July 2010 Rules. Since the introduction of these provisions until 2020, SIAC has recorded 94 emergency arbitrations.

Despite having only introduced emergency arbitration in 2012, up to the end of 2019, the ICC had registered 117 emergency arbitrations.

HKIAC introduced emergency arbitration proceedings in 2013 and has reported a total of 13 cases up to 2020.

The LCIA was the last to announce the adoption of emergency arbitration procedures – effective as of 1 October 2014. Up to 1 January 2020, the LCIA had reported a total of 6 emergency arbitrations.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the ICC's higher caseload, this institution has seen the largest use of its emergency arbitration function. One important note to the SIAC figures, which represent the second most active institution for emergency arbitration, is that unlike the other institutional rules amendments, the SIAC rules provided for the retrospective application of its emergency arbitration provisions to agreements entered into before those provisions were introduced. This may in part explain the high numbers from SIAC, alongside its relatively early introduction.

Turning to the prospects of success, the LCIA figures appear consistent with the SCC's statistics – the LCIA has recorded 50% successful applications (3), 33% dismissed (2) and 17% withdrawn (1). In contrast, on a first glance, the prospects appear significantly higher for parties before an HKIAC emergency arbitration. For the 11 emergency arbitrations post-2014 before the HKIAC, 82% (9) have been successful, 9% (1) has been unsuccessful and 9% (1) has been withdrawn by the applicant (9%). However, parties should be wary of putting too much weight on this analysis given the small case numbers involved. Only time and usage will reveal of this is a genuine differentiator.

Unfortunately, we do not have accessible information regarding the result of SIAC emergency arbitration. However, the ICC has released its own report on emergency arbitration proceedings which examined the 80 emergency arbitration applications filed between 2012 and the end of 2018. Of the 80 applications, 45% (36) applications were entirely dismissed, 29% (23) were successful (or partially successful), and 26% (21) were withdrawn or not accepted due to jurisdiction/admissibility issues.

This mixed set of outcomes will come as no surprise to practitioners aware of the difficulties in overcoming the exceptional nature of interim measures applications.

A successful innovation

Despite the small sample sizes, and the difficulty of drawing conclusions across institutions with differing approaches, and – to some extent – differing client bases, it is appropriate to attempt some conclusions from the first 10 years of modern emergency arbitration.

First, emergency arbitration has been welcomed, through being adopted, by users of international arbitration. Despite question marks around the enforceability of emergency arbitrator decisions, the enthusiasm with which emergency arbitration has been taken up by clients and arbitration counsel, as also reflected in the broad adoption of an emergency arbitration procedure as institutional best practice, is testament to a successful innovation.

Second, there is no apparent predisposition for applications either to be granted or dismissed. Rather, the evenly balanced outcomes across the available data suggest a process that, while time-bound, considers applications on their merits and produces a mixed range of outcomes suggestive of a proper application of legal principles to the facts at hand. Certainly, this is also the experience of the authors from their involvement in cases across several institutions.

Third, knowledge of the existence, opportunities and limitations of emergency arbitration is now a necessary and important part of the armoury of any international arbitration counsel both in commercial and investment treaty cases. Alongside the possibility of interim measures from a national court (and recognising too that the availability of emergency arbitration may in some cases affect the attitude of national courts; see, for example, the English case of Gerald Metals v Timis), the potential for emergency arbitration should be considered at the outset of any case calling for urgent relief.

Truly, an innovation and an anniversary to be noted and applauded.

This article was first published on Global Arbitration Review on 15 June 2020

For more information, please contact Nick Peacock, Partner, Jake Savile-Tucker, Associate, or your usual Herbert Smith Freehills contact.

Disclaimer

The articles published on this website, current at the dates of publication set out above, are for reference purposes only. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action.