This article is a part of our Remediation Round-Up series which explores potential issues for financial services licensees when conducting remediation and ways to optimise the design of remediation programs.

Issues to consider

- The selection of a remediation period is a critical decision in the development of a remediation plan, and will depend on a range of factors including risk, liability and reputational issues.

- Licensees must avoid unnecessary delays, as this may indicate that licensees have not allocated adequate resources to conduct the remediation

Selection of timeframe for remediation

The selection of a timeframe is an integral part of any remediation. This involves the licensee considering the period of time during which the relevant misconduct or other compliance failure may have occurred, and making a decision on the time period for which it will remediate. The following considerations are relevant in selecting a timeframe:

- availability of accurate records regarding the subject of the remediation, noting that licensees are required to keep certain records in relation to the provision of financial services for at least seven years;

- applicable statute of limitation period (discussed below);

- whether the loss is ongoing;

- any potential reputational issues that may arise should remediation not occur; and

- scale and significance of the misconduct.

In RG 256, ASIC has stated that it generally does not expect licensees to review advice given to clients more than seven years before it became aware of the misconduct or other compliance failure.

However, ASIC expects that licensees will act in a way that gives priority to the interests of clients when deciding a remediation timeframe. In this regard, ASIC noted that in certain circumstances, it may be appropriate to review records going back further than seven years.

Similar approaches can be undertaken in relation to remediation programs that apply with respect to other financial products. For example, where an error in a bank’s loan book system causes miscalculations with respect to client’s interest payments for the entire duration of the loan, it may be appropriate to remediate the client’s loss for the entire duration of the loan, even if the loan is more than seven years old. Similarly, an error in the calculation of annual premiums for a life insurance product may need to be remediated by reference to the overpayment that applied for the entire lifetime of the product until the issuer became aware of the error.

In May 2020, ASIC announced a review of RG 256, with a view to ensuring that it applies to remediation across the entire financial services sector. Accordingly, ASIC’s views in RG 256 are likely to become more instructive across a range of remediation programs beyond financial advice.

Statute of limitations and AFCA jurisdiction

As outlined above, the statute of limitation period is an important factor when determining a timeframe for remediation. This is because a strict legal obligation to remediate may no longer exist with respect to a loss for which the statute of limitation period has already expired (as the relevant cause of action will have expired). However, licensees should keep in mind that ASIC expects that licensees will act in a way that gives priority to the interests of clients and should therefore consider whether its decision to not remediate losses for which the statute of limitation period has expired could potentially attract ASIC’s scrutiny, as well as result in adverse reputational consequences.

Further, AFCA may use its discretion to consider a complaint for which legal proceedings have already been instituted by the complainant if the relevant limitation period will shortly expire, provided that the complainant undertakes in writing to AFCA not to take any further steps in the proceedings while AFCA is considering the complaint, even though it is AFCA’s ordinary practice to not consider a complaint while legal proceedings with respect to the same subject matter is on foot.

Limitation periods

We have outlined the relevant limitation periods for common causes of action below.

| Cause of action | Limitation period | When the limitation period starts |

| Breach of contract for breach of simple agreements. | Six years | From the point of breach |

| Damages under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), including for breach of industry code. | Six years | After the day on which the cause of action that relates to the conduct accrued. |

| Damages for misleading conduct. | Six years | After the day on which the cause of action that relates to the conduct accrued. |

| Compensation orders for breach of a civil penalty provision under Corporations Act. | Six years | From the date of contravention. |

| Negligence claims | Six years | After the action rises, meaning when actual or ascertainable damage occurs. |

In New South Wales, there is also a general provision which sets an ultimate time bar for limitations purposes, otherwise known as a “long stop provision”. Section 51(1) of the Limitation Act 1969 (NSW) provides that an action on a cause of action for which a limitation period is fixed by the Limitation Act 1969 is not maintainable if brought after the expiration of a limitation period of thirty years running from the date from which the limitation period for that cause of action runs. The only exception is for a cause of action for which an order has been made to extend time for latent injury, which acknowledges that some types of injuries may only be manifest over a period exceeding 30 years – this is discussed below.

It is also important to bear in mind that the interaction between limitation periods and equitable causes of action is not straightforward, and will often require complex analysis with respect to when the limitation period runs from.

Modifications to limitation periods

There are potential modifications to the period of limitations depending on the facts of particular cases. For example, in certain cases time may not run for limitations purposes if the damage already suffered was not discoverable by the plaintiff within the limitation period. This approach has been adopted by statute in relation to latent personal injuries, as well as in case law in relation to latent building and title defects.[1]

However, there has been general resistance in adopting similar approaches in relation to other causes of action. As Deane J explained in Hawkins v Clayton:

“Commonly in [building] cases, the building never existed and was never owned without the defect and (in the absence of consequential collapse or physical damage or injury) the only loss which could have been sustained by the owner was the economic loss which would be involved if and when the defect was actually discovered or became manifest, in the sense of being discoverable by reasonable diligence, with the consequence that the damage was then sustained by the then owner … The position is different in cases where all or some of the damage, be it in the form of physical injury to person or property or present economic loss, is directly sustained in the sense that it does not merely reflect diminution in value or other consequential damage which occurs or is sustained only when a latent defect which has existed at all relevant times becomes manifest. In those cases, damage is sustained when it is inflicted or first suffered and the cause of action accrues at that time.”

This distinction is also observable in Mulcahy v Hydro-Electric Commission, where the Federal Court of Australia found that the cause of action accrued normally and not when the plaintiff became aware of the fact that the defendant employer failed to notify the plaintiff employees of their statutory right to elect to contribute to a fund, as the critical knowledge was reasonably discoverable and therefore not comparable to a hidden crack in the building, as the case is in defective building cases.[2]

Further, the running of time for limitation purposes may be suspended in the event that the plaintiff suffers a disability or where the cause of action is deliberately or fraudulently concealed.[3]

Complaints to AFCA

As mentioned, AFCA’s jurisdiction is also a relevant consideration in determining an appropriate remediation period.

Under AFCA’s Complaint Resolution Scheme Rules, AFCA will not consider a complaint unless it was submitted to AFCA before the earlier of the following time limits:

- within six years of the date when the complainant first became aware (or should reasonably have become aware) that they suffered the loss; and

- where the complaint was given an IDR response prior to submitting the complaint to AFCA, within two years of the date of that IDR response.

Special rules apply with respect to superannuation complaints and complaints to which the National Credit Code apply. For superannuation complaints, the following limitations apply:

- for complaints with respect to the payment of a death benefit, AFCA will only consider a complaint if the complainant objected to the licensee within 28 days of being given notice of the proposed decision. The time limit for this complaint is 28 days from the financial decision;

- for complaints about statements given by the licensee to the Commissioner of Taxation, the time limit is 12 months from the date of notice; and

- for all other superannuation complaints including where the complainant has an interest in the death benefit, but was not properly notified of the proposed payment or the objection period, the time limit is two years from the IDR response.

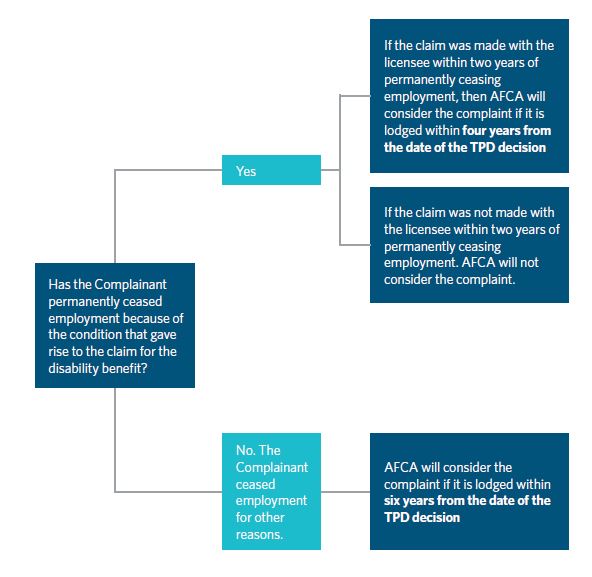

For superannuation complaints with respect to total permanent disability (TPD) decisions by the trustee, RSA provider or insurer, the following diagram illustrates the time limits that apply:

For financial hardship, unjust transaction or unconscionable interest and other charges under the National Credit Code, the complaint must be submitted by the later of:

- when the credit contract is rescinded, discharged or otherwise come to an end, two years from the contract end; and

- when an IDR response was provided, two years from the IDR response.

ASIC expectations on implementation

In addition to the foundational expectation that licensees will act in a way that gives priority to the interests of clients, ASIC also expects licensees to ensure any remediation is conducted in an efficient and timely way by the licensee allocating adequate resources to any remediation program.

ASIC is more likely to closely scrutinise the remediation program if the timeframe for remediating clients is lengthy, taking into account the nature of the misconduct or other compliance failure and the number of affected clients.

Unnecessary delays may indicate that the licensee does not have adequate resources to conduct the review and remediation, or that the licensee is not prioritising the remediation of clients and acting efficiently, honestly and fairly.

It is in the licensee’s interests to remediate in a timely manner, as delayed remediation could increase the amount of interest it must pay to compensate for foregone returns or interest (i.e. time value for money), noting that where it is not reasonably practicable to determine the actual investment returns or interest, ASIC considers it is appropriate to use the cash rate set by RBA plus 6%.

[1] See, for example, section 50D of the Limitation Act 1969 (NSW); Sutherland Shire Council v Heyman (1985) 157 CLR 424; Cyril Smith & Associates Pty Ltd v Owners Strata Plan No 64970 [2011] NSWCA 181.

[2] (1998) 85 FCR 170 at 245.

[3] See, for example, Limitation Act 1969 (NSW) s 52.

Key contacts

Disclaimer

The articles published on this website, current at the dates of publication set out above, are for reference purposes only. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action.