On 24 June 2021, an international panel of legal experts (the Panel) published a legal definition of 'ecocide' (the Proposal, link) proposed to be adopted as a fifth crime to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (the ICC or the Court). The Rome Statute addresses crimes that are deemed to be of international concern: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression. The ICC complements the jurisdiction of national criminal legal systems, and does not replace them (see Article 1, Rome Statute). The Court prosecutes cases as a court of "last resort", only when States are unwilling or unable to do so.

Ecocide is defined as "unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts". If the Rome Statute were amended to include ecocide, individuals (including corporate officers and State officials) could potentially be prosecuted by the ICC for such acts falling within the ICC's jurisdiction. Amendment of the Rome Statute is not a straightforward process, requiring a two-thirds vote of its existing member States. However, the adoption of this new definition may in any event lead to an increasing number of States coming to recognise a crime of ecocide under their domestic law.

HISTORY

Arguments for the recognition of ecocide as an international crime have a long history. The Panel's work was inspired by earlier efforts. The first reference to ecocide can be traced back to 1970, when the term was used by Professor Arthur W. Galston in the context of the environmental damage and other harms caused by the use of Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. In 1972, at the UN Conference on the Human Environment, Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme referred to the idea of ecocide as an international crime. In 1985, an unsuccessful attempt was made to add ecocide to the Genocide Convention. Almost a decade later, the UN's International Law Commission decided, after careful consideration, not to include environmental crime as an independent crime in its Code of Crimes Against the Peace and Security of Mankind, which later formed the basis of the Rome Statute.

The proposal that the ICC should play a role in prosecuting persons who cause major environmental damage is also not entirely novel. In 2016, the ICC's Office of the Prosecutor under former ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, published a policy stating that the ICC would prioritise the prosecution of war crimes involving destruction of the environment, illegal exploitation of natural resources and land-grabbing (see our previous post here).

PROPOSED DEFINITION

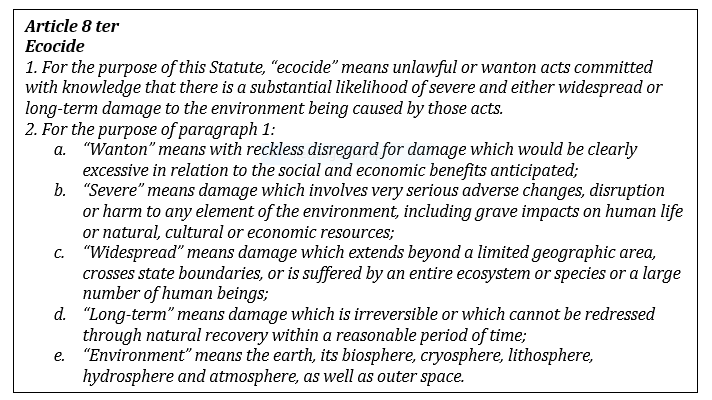

The Proposal is to: (i) amend the preamble to the Rome Statute to include a recognition “that the environment is daily threatened by severe destruction and deterioration, gravely endangering natural and human systems worldwide”; (ii) add ecocide to the list of crimes in Article 5; and (iii) include the definition of ecocide in Article 8.

The grave nature of the proposed crime of ecocide is reflected by the following cumulative elements of the crime: (i) the act (single or cumulative acts or omissions) needs to be unlawful or wanton; (ii) there needs to be knowledge of a substantial likelihood of damage that is severe and either widespread or long-term; and, (iii) the damage of which there is a substantial likelihood needs to be caused to the environment by the act.

Unlawful or wanton acts

‘Unlawful’ captures environmentally harmful acts that are already prohibited by either domestic or international laws.

As described by the Panel, "wanton" is a concept already used in international criminal law to mean either "intending or in reckless disregard of prohibited consequences". The prohibited consequence in this case is damage to the environment which would be clearly excessive in relation to the social and economic benefits anticipated. This introduces a proportionality test into the definition which balances environmental harms against social and economic benefits, consistent with much of domestic and international environmental law.

Severe and either widespread or long-term

'Severe' constitutes a sufficient harm threshold for the purpose of the crime of ecocide. The damage to the environment must also be either widespread or long-term. 'Widespread' relates to a geographical area but also includes an anthropocentric concept of widespread, i.e. 'a large number of human beings'. 'Long-term' on the other hand refers to the temporal nature of the damage. The standard is purposefully kept vague, and does not require waiting for the reasonable period of time to elapse before a prosecution could be brought. What constitutes a ‘reasonable period of time’ will depend on the particular circumstances of any situation. In any event, the ‘knowledge of substantial likelihood’ will be met where it is evident that the damage is likely to be irreversible and carry long term effects, or unable to be redressed in a reasonable period of time.

Environment

'Environment' is given a wide definition, encompassing earth and outer space, as well as the lithosphere (the interior and surface of Earth); the biosphere, (that part of the planet that can support living things); the hydrosphere (areas covered with water); the atmosphere (an envelope of gas); and the cryosphere (ice at the poles and elsewhere).

Mens rea and culpability

Article 30 of the Rome Statute provides that criminal intent exists where a person intends to cause a particular consequence or is aware that it will occur in the ordinary course of events. The Proposal argues for a lower threshold of 'knowledge of substantial likelihood' and that recklessness as to the consequences of one's actions should be sufficient to establish an intent to commit the crime of ecocide.

This also means that culpability for the proposed crime of ecocide would potentially attach to the creation of a dangerous situation, rather than a particular outcome. It is the commission of acts with knowledge of the substantial likelihood that they will cause severe and either widespread or long-term damage that is criminalised. The crime of ecocide is thus formulated in the Proposal as a crime of endangerment rather than of material result.

APPLICATION TO LEGAL PERSONS, INCLUDING CORPORATES?

The ICC has jurisdiction over natural persons only. Where corporate involvement in the crime of ecocide were alleged, it would need to be established that the relevant corporate officers bore individual criminal responsibility for the crime, posing considerable practical and evidential hurdles. The ICC does not currently have jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute corporations themselves, and the Rome Statute would need to be amended to facilitate prosecution of corporations for ecocide. The Proposal itself does not argue for such an amendment, but there have been other calls for the ICC's jurisdiction to be extended in this way.

The ICC also has a limited geographical and temporal jurisdiction. It can only exercise jurisdiction over crimes committed after 1 July 2002 by an individual in the territory of a State Party to the Rome Statute or by nationals of a State Party.

The indirect risks for a corporation of being associated with an investigation into any of the crimes that fall within the ICC's jurisdiction, however, are many and varied, from reputational and financial risk to potential domestic prosecution and risk of civil litigation.

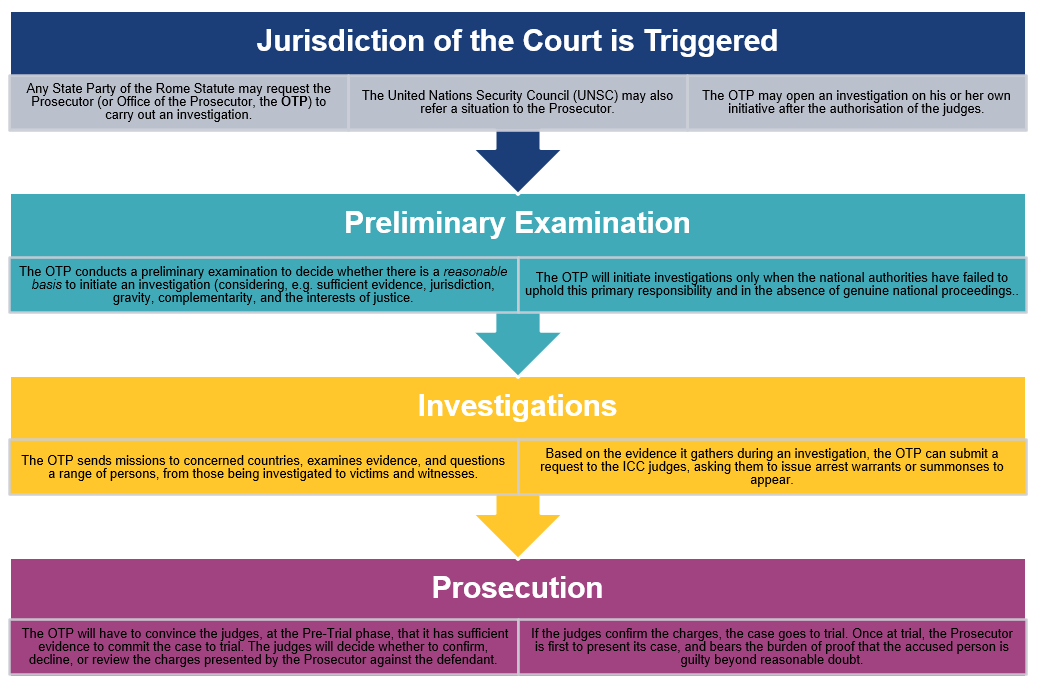

EXERCISE BY THE COURT OF ITS COMPLEMENTARY JURISDICTION

The "complementarity" of the ICC, as set down in the Preamble and Article 1 of the Rome Statute, is fundamental to the Court's functions. The ICC is a court of last resort. As such, it deals with cases of egregious wrongs under only limited circumstances, where the relevant State is unable or unwilling to prosecute an accused person.

The principle is encapsulated in Article 17 of the Rome Statute, which provides that the Court must determine that a case is inadmissible where:

- the case is being investigated or prosecuted by a State which has jurisdiction over it, unless the State is unwilling or unable genuinely to carry out the investigation or prosecution;

- the case has been investigated by a State which has jurisdiction over it and the State has decided not to prosecute the person concerned, unless the decision resulted from the unwillingness or inability of the State genuinely to prosecute;

- the person concerned has already been tried for conduct which is the subject of the complaint; or

- the case is not of sufficient gravity to justify further action by the Court.

There is a detailed procedure before a case comes before the Court:

There have been 30 cases before the ICC to date, with some cases involving more than one defendant.

AMENDMENTS TO THE ROME STATUTE

Amending the Rome Statute to adopt the crime of ecocide would require the following steps (under Article 121):

- A proposal to amend by any State which has ratified the Rome Statute. There are currently 123 member States to the Rome Statute. As noted below, a number of States have expressed support for the proposal who may individually or collectively put forward a proposal.

- The Assembly of the ICC must decide by majority of those present whether to take up the proposal. The ICC Assembly works on a one-State, one-vote basis, so each State has equal voting power.

- A Crime Review Conference may then be convened, or negotiation may progress via formal and informal discussion between representatives of member States. With the agreement of at least two thirds of member States (currently 82 out of 123) the amendment can be adopted into the Rome Statute.

- The amendment will only enter into force for States which have ratified the amendment. The ICC does not have jurisdiction regarding the crime covered by the amendment when committed by a member State's nationals or on a member State's territory if that member State has not ratified the amendment.

Assuming that a proposal is made, this process could take several years to complete. The amendment to the Rome Statute to include the crime of aggression, for example, was negotiated over a period of almost a decade.

SUPPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY

There has been some international support for the Proposal, predominantly from a number of European countries and Pacific Island States. In December 2019, Vanuatu and the Maldives called for serious consideration of an ecocide crime at the International Criminal Court’s assembly. Politicians from a number of countries, including France, Belgium, Finland and Luxembourg have publicly expressed their support for the initiative. Canada stated in Jan 2021 that it would "follow closely the discussions on ecocide at the international level". And in May 2021, the European Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee resolved to encourage “the EU and its Member States to take a bold initiative ... to pave the way within the International Criminal Court (ICC) towards new negotiations between the parties with a view to recognising ‘ecocide’ as an international crime under the Rome Statute”.

Despite this level of support, it is worth noting that a number of the major industrialised countries (such as the United States, China, India and Russia) are not parties to the Rome Statute.

COMMENT

As climate change and the impact of human activity on the environment have risen up the political agenda in countries around the world, the development of the Proposal can, on the one hand, be seen as a natural step towards ensuring greater accountability of all actors – State and non-State – whose actions cause significant environmental harm, including the physical and human effects of climate change. However, the differentiation of "ecocide" as a grave international crime (alongside the other serious crimes covered by the Rome Statute), as opposed to a civil wrong, represents a clear raising of the stakes. In particular, if the Rome Statute were to be amended, this would bring significant ramifications not only for decision-makers within businesses, but also for Governments who would need to consider the prospect that their decisions may give rise to international criminal liability for state officials. With regard to the latter, the threat may give rise to both broader policy change and even more careful scrutiny of specific decisions with potential environmental impacts.

Further, while change to the Rome Statute to include the crime of "ecocide" is a longer term prospect, the Proposal may give further impetus to other initiatives to expand both civil and criminal accountability for environmental harm, including relating to the effects or potential effects of climate change. For example, some States may be minded to adopt the definition of ecocide proposed by the Panel into their domestic law.

In the meantime, there are other proposals for the creation of new criminal offences in relation to conduct causing serious environmental harm. For example, the draft ESG due diligence directive prepared by the European Parliament's Legal Affairs Committee includes a recommendation that criminal sanctions be imposed by EU Member States for "severe cases" where a business has failed to act with due diligence to avoid adverse impacts on the environment and/or human rights. (Further detail on these developments in the EU is available here and here.)

In summary, this is an area in which significant development can continue to be expected, both at the domestic and the international level.

For more information, please contact Andrew Cannon, Partner, Christian Leathley, Partner, James Palmer, Partner, Craig Tevendale, Partner, Silke Goldberg, Partner, Benjamin Rubinstein, Partner, Antony Crockett, Partner, Hannah Ambrose, Senior Associate, or your usual Herbert Smith Freehills contact.

The authors would like to thank Jonas Thierens for his assistance in preparing this blog post.

Andrew Cannon

Partner, Global Co-Head of International Arbitration and of Public International Law, London

Christian Leathley

Partner, Co-Head of the Latin America Group, Co-Head of the Public International Law Group, US Head of International Arbitration, London

Key contacts

Andrew Cannon

Partner, Global Co-Head of International Arbitration and of Public International Law, London

Christian Leathley

Partner, Co-Head of the Latin America Group, Co-Head of the Public International Law Group, US Head of International Arbitration, London

Disclaimer

The articles published on this website, current at the dates of publication set out above, are for reference purposes only. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action.