Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

Pre-emption clauses are a common feature of joint venture agreements, particularly in the energy and natural resources sector. Despite their complexity and significance, such clauses are at times given little attention when the agreement is being drafted. When this happens, joint venture parties should not be surprised that disputes arise concerning the proper construction and application of the pre-emption clause. Here, Paula Hodges QC, Konrad de Kerloy and Ante Golem discuss.

Pre-emption clauses typically prohibit a joint venture participant from disposing of its interest in the joint-venture without first offering its fellow joint venturers the opportunity to acquire that interest. However, with careful drafting, this requirement can be made subject to certain caveats, such as a change of control or a transfer to a related entity.

The underlying objective of pre-emption clauses is to prevent a new third party joining the joint venture without the approval of the other joint venturers. To that extent, the provisions resemble a clause that limits free assignment of interests. The difference between the two types of restriction is that pre-emption provisions also provide the opportunity for one of the other joint venturers to purchase a bigger piece of the action and this has the potential to alter the dynamic within the joint venture significantly. This possibility, coupled with the alternative of admitting a new party into the joint venture, can raise corporate temperatures and lead to hard fought disputes.

Given the aim of pre-emption clauses to police the entry of third parties to the joint venture, certain exceptions can be carved out to cover circumstances where the exiting party wishes to transfer its interest to an affiliate or where a third party is purchasing the exiting company as a whole resulting in a change of control. The justification is that in both cases, the corporate identity of the exiting co-venturer is not changing significantly and it is not being substituted with a completely new third party.

Recently, one of our clients was faced with a very difficult situation emanating from the pre-emption provisions, which threatened the future of the joint venture project. When the joint venture was put together, the participants intended to get the project up and running and then introduce a third party with both deeper experience of oil and gas exploration and downstream LNG facilities, and deeper pockets to inject additional investment into the project. However, when our client, as operator of the project, sought to introduce such a third party, the other major joint venturer objected and threatened to use the pre-emption provisions to stymie the deal. The deadlock that ensued began to impact the progress of the project and jeopardised completion of the deadlines set by the host government in the licence agreement.

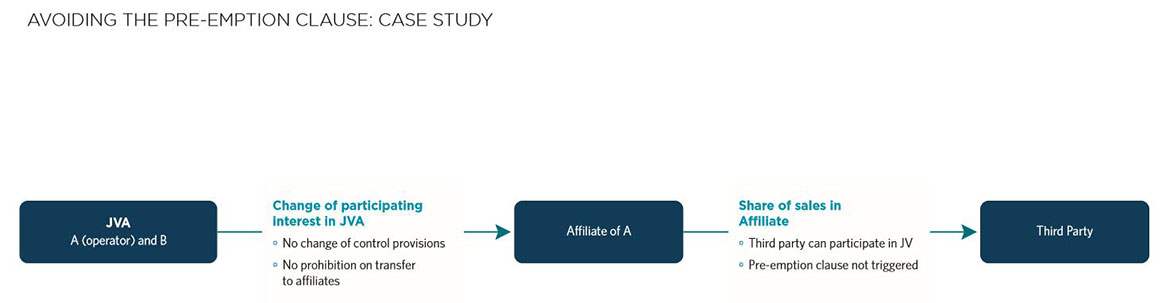

Our client turned to us for advice and, on reviewing the contract in question, we discovered that the pre-emption provisions exempted both change of control transactions and transfers to affiliates. We therefore advised our client to structure the deal as two separate transactions. The first step consisted of the transfer of part of our client's participating interest to an affiliate entity, followed by the sale of the shares in that affiliate to the third party wishing to join the project.

The deal went ahead and was challenged by the other major joint venturer on the basis that the pre-emption provisions should bite given the overall intention to transfer the interest to a new third party. They argued that the tribunal should apply the spirit of the pre-emption provisions, and not just the letter of them.

ICC arbitration proceedings were commenced, but the tribunal upheld the combined deal as permissible given that it consisted of two separate transactions, both of which were exempted from the application of the pre-emption provisions.

The end result was that the participating interests were kept within the (albeit extended) family and the project is now proceeding apace.

Practical implicationsJoint-venture parties should bear in mind that:

|

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2025

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs