Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

As countries around the world move to lower carbon economies and take steps to protect financial systems from “climate change” risk, there is a real prospect of regulatory action and private litigation against financial institutions that fail to prepare for and (if necessary) disclose the costs to their business of the move to this low carbon norm; and who take insufficient steps to mitigate against their direct and indirect exposure to damaging “climate events”.

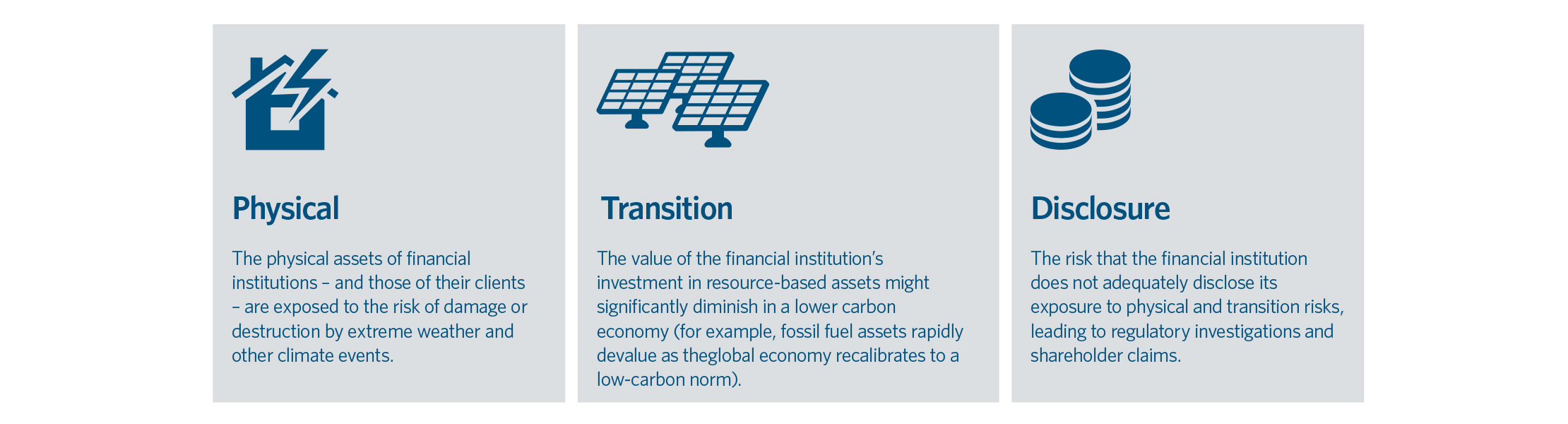

Financial institutions face three primary climate change risks:

Not only is the increased frequency of climate events a direct threat to asset value, a range of indirect costs can arise when assets are physically impacted by climate change, including increased insurance claims and portfolio losses, a decrease in investments’ value, an increased risk of loan defaults and broader systemic shocks such as economic disruption and lower productivity.

The assessment of such physical risks by financial institutions is often done in isolation and not as part of a broader climate change assessment which could impact mitigation strategies.

A consequence of this risk could be that financial institutions seek to limit their losses by reducing their exposure and restricting lending and credit to companies and sectors with a high climate risk. The need to protect against physical risks is in part being recognised by the increasing number of financial institutions in recent years agreeing to implement the Equator Principles in relation to their investment decisions (discussed further below).

There are costs for all sectors, including financial institutions, associated with the transition to a low carbon economy, including the impact on asset valuation, costs of implementing government policy changes, adoption of technological developments and changes to market sentiment that might influence how a financial institution markets itself or targets projects of clients.

A key risk is where financial institutions have investment exposure to resources directly impacted by a move to a low carbon economy – for example, fossil fuel could rapidly re-price with booked reserves becoming unrealisable at historical valuations.

This risk is compounded with the implementation of accords such as the Paris Agreement under which 196 countries have agreed to introduce policies to limit global warming to no more than 2°C above pre-industrial average temperatures.

Meeting this target alone could require a significant proportion of “proven” fossil fuel reserves currently sitting on corporate balance sheets to remain in the ground, implying marked devaluation (or, in extreme cases, the writing-off) of those assets as Paris commitments are implemented. This could have significant implications for the value of financial institutions’ investments and the clients they support.

Financial institutions that are not prepared for transition risk may face the devaluation of their investment portfolios or their balance sheets as the value of any collateral taken decreases or a borrower's business model and risk profile changes following government and market response to climate change.

This risk arises where financial institutions that are subject to continuous or periodic disclosure obligations fail to disclose their financial exposure to the physical and transition risks.

For example, the UK’s Financial Reporting Council has opened an examination into the adequacy of risk disclosures made in the annual reports of two oil and gas exploration companies listed on the London Stock Exchange. The investigations, which were prompted by complaints filed by public-interest bodies, focus on whether the two companies failed to inform the market about material economic costs associated with moving to a lower carbon environment in breach of their disclosure obligations under the UK Companies Act.

Similarly, the Securities and Exchange Commission is investigating whether ExxonMobil’s annual reports present a true and fair view of its financial position, particularly:

The Financial Stability Board, an international body that monitors and makes recommendations on the global financial system established after the 2009 G20 London summit, convened a task force on climate-related financial disclosures (TCFD).

The TCFD’s objective is to promote voluntary, consistent, comparable, reliable and clear disclosures around climate-related financial risk. The central idea is raising climate risk disclosure standards such that market participants will understand climate change related risks more clearly as they will have access to better quality information. Such an understanding may also contribute to a smooth market transition to a lower carbon economy.

Ninety financial institutions in 37 countries took steps to integrate environmental considerations into their financial decision-making with the adoption of the Equator Principles. These principles form a risk management framework used to assess and manage environmental and social risk in large projects.

The Equator Principles are now considered the industry standard and are applied globally to all projects where total project capital costs exceed US$10 million. Equator Principle financial institutions commit not to provide financing to borrowers which will not or cannot comply with their environmental and social policies and procedures, and to require borrowers for projects with greenhouse gas emissions above a certain threshold to implement technically and financially feasible measures to reduce such emissions.

In addition to assisting with risk assessment and management, these and similar measures amplify the effectiveness of government climate change policies by accelerating capital reallocation and investment in lower-carbon technology and practices.

|

Although financial institutions are increasingly aware of the need for steps to address climate risk, challenges remain.

A recent survey of prominent Australian companies, for example, noted that many financial institutions did not disclose exposure to climate risk or, where there was disclosure, the scale or type of risks disclosed were inconsistent with other companies operating in similar environments. Another study reviewed public disclosures of the 100 largest funds in Australia and found that 82% had disclosed little to no evidence that they were considering climate risk.

In coming years, all financial institutions around the globe will need to develop and/or review assessment and management of climate legal risk, including physical, transition and disclosure risk.

This article currently appears in the Global Bank Review 2017 publication.

To download a PDF of this article click Download above.

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2025

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs