Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

New technology is revolutionising the way we live, work and communicate.

The proliferation of fintech comes at a time when regulators across the globe are significantly increasing their oversight over the banking sector, implementing new regimes with personal accountability and financial consequences for senior managers and executives within banks. These regimes have been introduced in the UK and Hong Kong, with substantially similar regimes soon to reach Australia and potentially Singapore.

At least to start with, these regimes have not imposed, or do not propose to impose, a corresponding level of regulatory supervision over fintech companies which are not involved in regulated activities.

"While governmental and regulatory encouragement for innovation seems to be at its peak, is it now time to revisit this regulatory disparity?"

In the meantime, banks have started asking: what is the best way forward in the current regulatory environment, in light of these emerging fintech companies? Key learnings from the US have shown that perhaps the best way forward is to stop seeing fintech as “competitors” and to start considering them “partners”.

In the UK, the Financial Stability Board, the international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system, is currently assessing how the development of fintech might be affecting the resilience of the financial system, identifying risks (including systemic risks) associated with existing financial institutions and activities, and assessing how these may arise within the fintech sector.

Regulators are trying to balance opening up the market to new entrants and preventing systemic risk. Bank of England Governor, Mark Carney, believes that although “there is nothing new under the sun”, there needs to be a disciplined and consistent approach to similar activities undertaken by different institutions which give rise to the same financial stability risks.

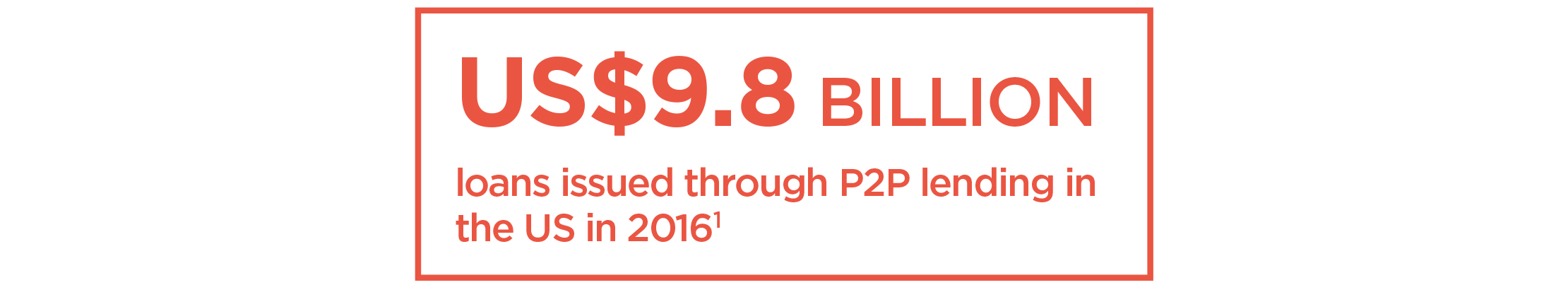

It is clear that some in the P2P sector are actively seeking out further regulation. Indeed, the UK regulator (the Financial Conduct Authority) signalled at the end of 2016, following a review into the sector, that it was looking to increase regulation due to concerns of a lack of regulation.

To some extent, the level of increased regulation will depend on whether it is acceptable for investors, through fintech, to bear more of the risk when compared to bank depositors. Even where investors accept that there is increased risk for them to bear in taking advantage of offerings such as P2P lending, there is always a distinction between acceptable and unacceptable risk (caused by failures within the organisation).

"UK, peer-to-peer (P2P) lending now represents around 15% of new lending to SMEs."

The question arises as to how such failures and unacceptable risk can be avoided, and how employees can be discouraged from acting in a way which might give rise to failures. Could senior employees, for example, be held personally accountable for their business areas as a way of increasing regulation and helping address (to some extent) where the risk profile lies within the fintech economy? Should there be direct financial and career-impacting consequences for those involved?

The global financial crisis and the UK regulator’s inability to take action against banking employees guilty of serious misconduct was one of the catalysts for the introduction of the Senior Managers and Certification Regime (SMCR) in March 2016, applying to deposit taking banks, building societies and credit unions.

The most senior employees in the bank, so-called “senior managers”, are now personally responsible for the area of the bank they run and are required to take reasonable steps to prevent regulatory breaches. The idea is that senior managers set the tone from the top, changing the culture and ensuring appropriate supervision of their area of the bank.

The Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards recommended implementation of the SMCR to obtain greater precision about individual responsibilities than the previous approved persons regime and as a means of upholding individual standards of behaviour. Ultimately, the UK regulator can take enforcement action against a senior manager personally and censure and fine them.

Our experience has shown that it has not always been a smooth road for the banks in encouraging senior employees to take on the role of a senior manager. In some cases, changes to reporting lines have been necessary to ensure those taking on a senior manager role have the requisite control over the business area for which they are now personally responsible. Banks have also received requests from senior managers for legal advice to understand the consequences of their new roles and requests for extended directors & officers insurance and indemnities to mitigate some of the risk.

The next level below senior managers are so-called “certified persons” whom the bank (rather than the regulator) must annually certify as fit and proper to undertake their role. These are people undertaking significant harm functions within the firm and are often individuals who were approved persons under the previous approved persons regime.

In addition, almost all employees are bound by conduct rules which apply a new standard of behaviour. This means acting with integrity, due skill, care and diligence, treating customers fairly (having regard to their interests), observing proper standards of market conduct and being cooperative with regulators. Breaches by employees are notified to the UK regulator.

Personal accountability as a concept is spreading through those jurisdictions with a large financial services sector.

In Hong Kong, the Managers in Charge regime (MIC) was introduced in December 2016, with MICs to be appointed by 17 July 2017. Similar to the UK senior managers regime, this regime contemplates that MICs, as part of senior management, should bear primary responsibility for ensuring the maintenance of appropriate standards of conduct and adherence to proper procedures by the firm. MICs may also be held personally responsible for failure within the business units for which they are responsible, taking into account the degree of responsibility they have and their apparent or actual authority in relation to the particular business operations. Like in the UK, the role of MIC is in addition to, and does not replace, the existing roles of the Board and the Responsible Officers of the firm.

Australia and potentially also Singapore are the next jurisdictions looking to introduce similar regimes. Our experience in assisting various banks with implementing the UK and Hong Kong regimes shows similar issues arise, regardless of the jurisdiction, where personal accountability is introduced: ensuring there is early buy-in from the senior employees who will take on personal responsibility (to avoid not being able to put them forward for the role and then having to restructure part of the business), tackling thorny issues like remuneration, insurance arrangements and indemnities, being prepared to answer the question of how the firm will help the employees comply with their role (what systems and controls are in place and what budget they have to ensure appropriate delegation, supervision and circulation of management information) and deciding how collective decision making can work within a personal accountability regime.

At least in the UK, the answer is “YES”! The SMCR is being extended from 2018 to all sectors of the financial services industry currently caught by the approved persons regime. This will include P2P lenders who are currently regulated by the UK's Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), as well as asset managers, hedge funds and wealth managers.

In July 2017, the FCA released its consultation paper confirming that the same broad structure will apply. In particular, firms will need to have senior managers who will be personally accountable for any failures in their business. In relation to “certified persons”, employees of P2P lenders, like Funding Circle and Zopa, who are currently subject to the approved persons regime will already be used to fitness and propriety assessments. Going forward, however, it will be the firm, not the regulator, making the assessment under the SMCR.

Will the UK start a trend for more personal accountability of fintech senior staff in other leading financial centres?

The MIC regime in Hong Kong is limited to licensed corporations who are subject to regulation by the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) (including fintech providers who undertake regulated activities in Hong Kong), and while it is expected that the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) will in time review its existing senior manager regime to align more closely with the MIC Regime, no plans to extend the provisions more broadly have been published.

The proposals in Australia are focused on the banks, rather than fintech companies.

It therefore seems the answer is “not yet”.

“Regulation [of banks] will continue and will probably get even tougher.”

David Gonski AC

Chairman of the ANZ Banking Group Limited

We asked John Walsh, Partner at McKinsey & Co and a specialist in US financial regulation, whether he thought such laws would be implemented in the US.

His answer was clear – in the current regulatory environment, legislation in this area is unlikely in the US and the country would most likely take a “wait and see” approach until and unless an incident of “egregious” conduct by a fintech company occurs.

Pertinently, Chairman of the ANZ Banking Group, Mr David Gonski AC, remarked on this trend of increased regulation stating that “regulation [of banks] will continue and will probably get even tougher.” In this vein, Mr Gonski considers that such regulation should be extended to fintech in Australia, emphasising the need to protect small consumers and that a failure to do so would result in tears.

The proposed new regulation in Australia of senior employees doesn’t just focus on personal accountability if something goes wrong, but also introduces more regulation of those employees’ remuneration. At this stage, there is scant detail, other than that up to 40% of variable remuneration will need to be deferred.

Deferral in itself is unlikely to drive behaviours, but what has been seen in other jurisdictions is the use of remuneration deferral as a mechanism to link remuneration to performance (by deferring into equity) and to provide an ability to reduce deferred amounts where past failures come to light.

In Europe, there has been stringent regulation on the remuneration of material risk takers in banks for several years, aimed at curbing excessive bonuses which were viewed as encouraging risky behaviour. Indeed, the UK regulators have gold plated the European regulations, requiring the deferral of senior bank employees’ remuneration for up to seven years during which time that remuneration is “at risk”, with at least half of it linked to share price movement. In addition, even once vested and paid, that remuneration remains at risk for up to a further ten years during which it may be clawed back by the bank.

While these arrangements apply to all European banks and investment firms (in particular those which have permission to hold client money), the rules have been implemented to apply on a “proportionate basis”: only the largest institutions need to apply the rules to the fullest extent, while smaller banks and investment firms may disapply many of the rules. There are, however, proposals to remove the ability for regulators to allow disapplication of the rules by all but the smallest firms. So it is likely that we will see greater levels of deferral in the future.

In Hong Kong, deferred bonuses which are subject to forfeiture and/or claw-back mechanisms are common in the financial services industry, although they are not mandated in the same way as in Europe. That said, both the HKMA and the SFC have adopted guidelines or otherwise encouraged firms they regulate to adopt remuneration practices which are consistent with the Financial Stability Board's Principles for Sound Compensation Practices and its implementation standards.

At least for the moment, many fintech companies, in particular P2P platform firms, have not been viewed as systemically important enough to require the rules to be extended to them. This may not continue to be the case as the industry develops. Indeed, within Europe, while the first wave of regulation affected banks and investment firms, it was not long before asset managers and insurers received their own set of regulations. Remuneration is always an agenda item, and it will only need the first failure within the fintech sector for minds to focus on this aspect of regulation.

As the SMCR does not deal with remuneration, the extension of the regime to all financial services institutions in the UK from 2018 means that the stick of personal accountability will apply but restrictions on remuneration will not. Will that be enough?

The regulatory disparity between banks and fintech regarding senior manager regimes is indicative of a more general regulatory trend in certain jurisdictions. Namely, a governmental and regulatory desire to promote innovation has seen a lack of regulation over fintech, and in some cases, a substantially more favourable regulatory treatment for fintech companies.

To take the Australian example, the government recently proposed legislative amendments that will expand the category of institutions permitted to describe themselves as “banks”. Currently this term is reserved for registered Authorised-Deposit Institutions (ADIs) with more than A$50 million in capital. The amendments propose to remove this capital requirement, allowing all ADIs to call themselves “banks” with a view to levelling the playing field for new entrants into the market, which could include small fintech companies engaging in banking business who are registered ADIs.

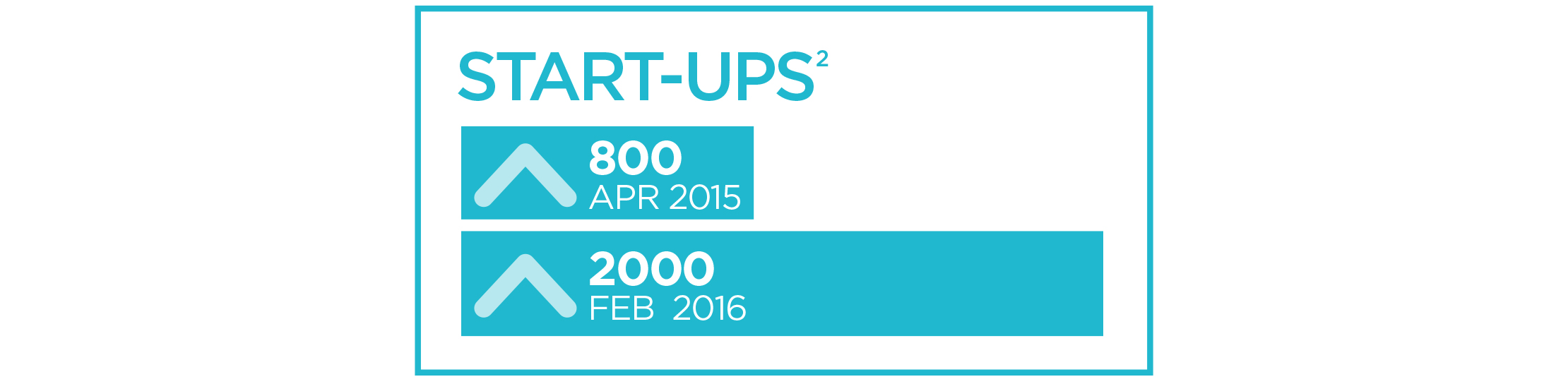

Other examples of this regulatory favouritism are in the form of tax incentives for early stage investors in start-ups and a fintech regulatory sandbox, which allows testing of new financial products and services to occur in a regulatory vacuum for the first 12 months. This idea is similar to that introduced by the UK’s FCA in 2015 which was taken up not only by fintech start-ups but also some of the largest banks wishing to test new products which do not fitwithin the current regulatory framework

Further, in the Australian crowd-funding space, a recently passed law allows public non-listed companies (worth less than A$25 million) to issue shares to retail investors without going through the usual IPO process, effectively exempting them from the usual corporate governance measures.

Interestingly, this regulatory disparity is not viewed as an issue by all, particularly those who consider the market is best placed to take care of a lot of the heavy lifting itself, specifically, where fintech users are able to determine the levels of acceptable and unacceptable risk they are willing to take on.

Ultimately, as put by McKinsey’s John Walsh, the fact that we are yet to see any egregious wrongdoing on behalf of fintech has meant that many regulators are taking a “wait and see” approach. While we will certainly see regulation in some parts of the world move towards applying to fintech, which would be a refreshing breath of regulatory fresh air, many jurisdictions are unlikely to cast such a broad net at this stage.

When considering the best way forward, we turned to several industry experts to gauge their thoughts. Mr Gonski explained that what fintech companies often forget is that, while they have good ideas, they need both capital and customers. This is what a big bank has to offer. Mr Gonski raised the growing trend of those strategically thinking fintech companies, who have realised that partnering with such a bank will improve their chances of success and longevity. In Mr Gonski’s opinion, we will start seeing more of these partnerships going forward which will, in turn, lead to banks meeting their technology aspirations and the increased accessibility of these new fintech ideas in the market. This is already being seen in the UK, with banks like RBS partnering with FreeAgent, Funding Circle and Assetz Capital. Mr Gonski further considered that this trend would increase with a more level regulatory playing field.

Mr Gonski explained that what fintech companies often forget is that, while they have good ideas, they need both capital and customers.

Mr Walsh agrees with this contention and believes that banks in the US are already “using and deploying” fintech companies through a range of structures, such as joint ventures, consortiums, acquisitions and service agreements. The fintech company takes care of the back and middle-ends, leaving the bank free to concentrate on the customer-facing front-end where they can really add value.

The best way forward seems to be for banks to enter into strategic partnerships with fintech companies, in order to benefit from their own capital and customer base, while leveraging the innovative ideas and technology of their fintech counterparts.

This article currently appears in the Global Bank Review 2017 publication.

To download a PDF of this article click Download above.

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2025

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs