Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

In this article, partner Nick Peacock and professional support consultants Vanessa Naish and Hannah Ambrose explore the availability of court-ordered interim relief in support of arbitration and how it interacts with the relief available within the arbitration process. They draw on recent developments and consider whether changes to institutional arbitration rules on emergency relief may have had unintended consequences for parties seeking to obtain interim relief from the courts.

First published in Inside Arbitration, Issue 5

Interim measures of protection (also known as interim relief or conservatory measures) are orders granted on a temporary basis in order to safeguard the rights of a party until there has been a final determination of a dispute.

In an increasingly globalised trading environment in which evidence and assets can often easily be transferred across borders, interim or conservatory relief is a significant aspect of effective dispute resolution. Interim relief may take many forms. A party may want to preserve the status quo (for example by restricting the transfer of shares, or the exercise of contractual rights in a permanent way), prevent the destruction of evidence, or ensure that any confidentiality obligations are observed. Most often, interim relief is aimed at preventing the dissipation of assets which are either the subject matter of the dispute or may be relevant to the satisfaction of an anticipated judgment or award.

The use of interim relief in litigation is well recognised. Yet interim relief is no less significant in international arbitration. The importance of timely and effective interim relief is recognised by the leading arbitration institutions including the ICC, LCIA, SIAC, SCC, Swiss Chambers, AAA-ICDR and

HKIAC. A number of these institutions will constitute an arbitral tribunal on an expedited basis to assist in cases of urgency. More recently, many institutions have introduced an emergency arbitrator (EA) facility: where an arbitrator is appointed for the sole purpose of determining urgent interim applications in a short timescale before the main tribunal is constituted.

Options for interim relief before an arbitral tribunal are therefore available. However, for many commercial parties, court-ordered interim relief may still be preferable. Court-ordered relief has a number of potential benefits, including the ability to seek ex parte relief, and to ensure that the relief binds third parties when that is needed to make it effective (for example, a freezing injunction against accounts held at third party banks).

The most natural forum for the grant of court-ordered interim relief in support of an arbitration is often the court of the seat of arbitration. In most jurisdictions which are regarded as supportive of international arbitration, the scope of the court's power

to grant interim relief is set out in the arbitration law of that jurisdiction, and the extent of this power is one important factor for parties to consider when choosing their seat of arbitration.

A further relevant consideration when choosing a seat is the type of interim relief available to ensure that, if a dispute arises, relief will be both effective and efficient. For example, where assets are spread across multiple jurisdictions, it may be time-consuming and inefficient to make multiple separate applications for relief in the courts of different jurisdictions, even assuming those courts would entertain such applications. A number of courts are empowered to grant a freezing order that extends to assets located outside of its jurisdiction. Worldwide freezing orders are available from the English court (and others) in support of arbitration and, indeed, have even been granted in circumstances where the seat was London but there were no assets within the jurisdiction (U&M Mining Zambia Ltd v Konkola Copper Mines Plc [2014] EWHC 3250 (Comm)).

It may be possible to seek anti-suit relief in anticipation of foreign court proceedings in breach of an arbitration agreement, even if no arbitration has been started. The English Supreme Court has been prepared to grant such relief (See Ust-Kamenogorsk Hydropower Plant JSC (Appellant) v AES Ust-Kamenogorsk Hydropower Plant LLP (Respondent) [2013] UKSC 35, where proceedings in Kazakhstan were threatened in breach of an agreement providing for arbitration in London).

Where should you make an interim relief application: arbitration or court?Key considerations Is interim relief in support of arbitration available in the courts which have jurisdiction over the counterparty and/or assets in question? Are there any restrictions on seeking court relief in the law of the seat? Does the application need to be made "ex parte" (ie without the other side being notified of the application in advance) in order for the measure to be effective? Is the relief sought urgent? If so, how urgent? Has the arbitral tribunal been constituted? If not, can you seek expedited constitution, or relief from an EA? Can a tribunal (or EA) act effectively in granting the relief sought (for example, does the relief sought need to bind third parties)? Would the counter-party be likely to comply with an order for interim relief from the tribunal? Would it comply with an order from the available court? Are there any restrictions in the arbitration agreement or the institutional arbitration rules on seeking interim relief? |

The courts of the seat will often be the most obvious forum in which to seek interim relief. However, in some cases, a party may be able to get effective relief from courts in another jurisdiction – for example, where the types of relief available are more advantageous, if the relief would be more effective if granted by the court of the respondent's domicile or where the relief is to protect assets which are located in another jurisdiction.

The courts of the seat will often be the most obvious forum in which to seek interim relief.

The statutory framework governing arbitration in a number of jurisdictions includes a power of the court to grant relief in support of arbitration proceedings wherever they are seated. The English court is able to grant interim relief where the seat of arbitration is outside England. Many other jurisdictions take the same approach, for instance, the Cypriot courts – a jurisdiction which is often used as a financial hub – also have this power. Commercial parties have used similar proceedings to good effect to obtain relief from the courts of the situs (for example, in the jurisdiction where physical assets are targeted by the interim relief application, or the jurisdiction where a debt is due to the respondent which the applicant wishes to attach).

However, the possibility of "forum shopping" for interim relief outside the court of the seat should not be exaggerated. Even though a court may have the power to grant relief, it may not consider it appropriate to exercise that power. The English court recently dismissed an application for interim relief where there was already litigation in the BVI and arbitration proceedings seated in Switzerland (see Company 1 v Company 2 and another [2017] EWHC 2319 (QB)). Its reasons for doing so included the tenuous link which the dispute had to England and the guiding principle that the natural court for granting interim injunctive relief is the court of the country of the seat of arbitration.

A further consideration is whether there are any restrictions in the parties' arbitration agreement which would preclude an application for interim relief to the courts other than the courts of the seat. These restrictions may be express. However, restrictions may also have taken effect by virtue of the parties' choice of institutional arbitration rules, as discussed further below.

Emergency arbitrator provisions or the scope for the expedited constitution of a tribunal may affect the court's power to order interim relief

The inclusion of EA provisions in all major institutional arbitration rules was heralded as the answer to the need for easy access to emergency relief within the arbitration process. EA provisions are useful where the available courts do not have procedures for granting interim or conservatory measures in support of an arbitration; or where parties prefer to make such an application within the arbitration. In promoting its emergency procedures, the LCIA explains that the EA provisions do not prejudice "a party’s right to seek interim relief from any available court" (see the LCIA Notes on Emergency Procedures). Similar statements have been made by other arbitration institutions in respect of their own EA provisions. Institutions have also included or expanded the availability of expedited arbitrations or the expedited formation of tribunals, which can ensure quicker access to interim relief from the tribunal.

Whilst it may not have been the intention in taking these initiatives to prejudice applications to the court for interim relief, a case last year in the English courts demonstrated that the availability of emergency relief within the arbitral process (including the possibility of expedited constitution of a tribunal) could indeed impact not only the court's balancing of the relevant circumstances concerning an application, but the court's powers to grant relief.

In Gerald Metals SA v Timis [2016] EWHC 2327 (Ch), the English court considered its power to order urgent relief under the English Arbitration Act in circumstances where the LCIA had already considered, and refused, an application to appoint an emergency arbitrator. The court found that the test of "urgency" under s44(3) of the English Arbitration Act 1996 would not be satisfied unless:

In this case, the court considered that, because the application for appointment of an emergency arbitrator had already been considered and dismissed by the LCIA Court, the test of urgency was not satisfied and therefore the court had no power to grant urgent relief under s44(3). The case is discussed in more detail on our arbitration blog here.

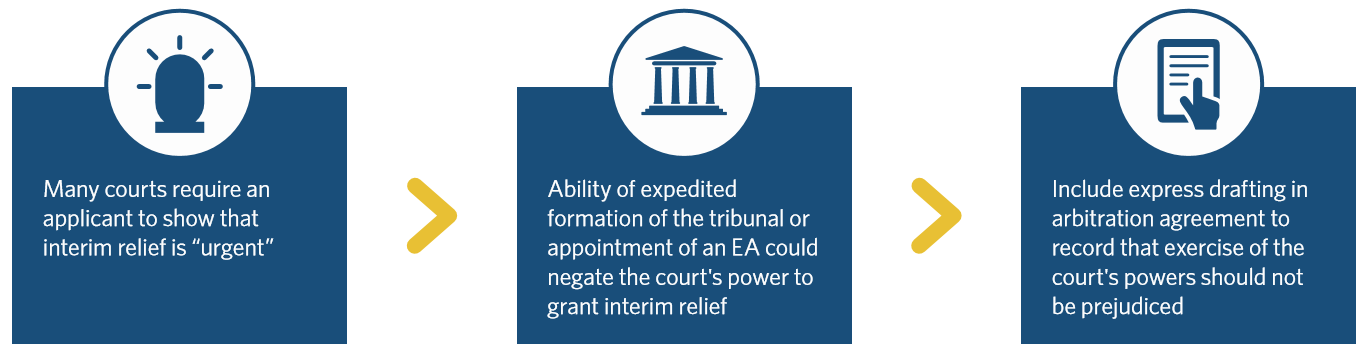

This case concerned the LCIA Rules and how they interact with the requirements of the English Arbitration Act 1996. However, the case has far broader application. As noted above, most institutional arbitration rules contain provisions dealing with emergency proceedings – either EA provisions or the ability to seek expedited constitution of a tribunal. Furthermore, many courts will require an applicant for interim relief to establish that the relief sought is urgent before they are empowered to grant it. As in the case of Gerald Metals, the combination of emergency provisions in the arbitration rules and carefully circumscribed powers of the court could prove fatal to an application for interim relief.

The inclusion of EA provisions in all major institutional arbitration rules was heralded as the answer to the need for easy access to emergency relief within the arbitration process.

So, can parties have it both ways – keep the EA provisions but without undermining the prospects of an application for interim relief from the courts? It is untested, but the most practical solution may be to include express drafting in the arbitration agreement which seeks to deal with the possibility that a party chooses to bypass the EA procedure, or is not successful in having an EA appointed. Suggested language could record that: neither (i) the potential availability of relief from an EA or the possibility of the expedited constitution of an arbitral tribunal; nor (ii) the failure to make an application for the appointment of an EA or expedited constitution, shall prejudice an application to a state court for interim relief. A further step could be to agree that the decision of the institution on whether to appoint an EA or to expedite constitution of the tribunal, or the decision of an EA on the question of whether the relief should be granted, shall not bind the court or limit its powers, thereby encouraging any court to reach its own conclusion on the facts of the application presented to it. Another option, of course, would be for the parties to exclude the emergency provisions of the institutional rules altogether. Arguably this would be the only effective approach where it is the existence of the mechanisms (rather than any evidence of whether or how they have been invoked) which would go to the jurisdiction of a court to hear an application for interim or emergency relief. Either kind of agreement should be considered carefully. It will be relevant to consider both the specific provisions of the law of the seat and the institutional rules, as well as the potential importance of access to EA relief or expedited constitution of the tribunal if disputes should arise.

In 2014 the LCIA launched its revised Arbitration Rules which introduced changes to the text of Article 25.3, which deals with the parties' right to apply to a state court for interim measures. This provision follows Article 25.1 which sets out the arbitral tribunal's own powers to grant interim or conservatory relief. An application to a state court after formation of the tribunal was permitted by the 2008 Rules "in exceptional cases". The changes to Article 25.3 in the 2014 Rules now explicitly focus on interim and conservatory measures "to similar effect" to those available under Article 25.1, but introduced an additional requirement that applications to a state court after formation of the tribunal may only be made "in exceptional cases and with the tribunal's authorisation".

Whilst there is an inherent appeal in seeking to ensure that the tribunal (once constituted) becomes the gatekeeper for the parties' applications for relief related to the proceedings (as is expressly envisaged by some arbitration legislation, for example, s44(3) of the English Arbitration Act 1996, and section 12(A)(6) of the Singapore International Arbitration Act Cap. 143A and more obliquely referred to in others, for example, Article 17J of the UNCITRAL Model Law), problems emerge where a need for such relief arises which is both urgent and involves seeking relief that – while "to similar effect" to that which may be granted under Article 25.1 - is beyond the ability of the tribunal to grant. A sensible reading of Article 25.3 is that it does not require the tribunal to authorise an application to the court for relief that the tribunal itself could not grant (ie relief which is not "to similar effect" to relief which the tribunal is empowered to grant under Article 25.1). A worldwide freezing injunction, for example, is arguably not "to similar effect" as the types of relief which the tribunal is empowered to grant under Article 25.1. However, on its face, Article 25.3 has the potential to cause difficulties for parties seeking urgent, and in particular without notice (ex parte), relief from a state court where that relief may fall within the scope of Article 25.1 or could be regarded as relief "to similar effect".

Moreover, tribunals have interpreted Article 25.3 as introducing a gateway whereby a party is required to establish that the case is "exceptional" (a subjective term which may or may not be equated with urgency) and then address the tribunal as to whether it should authorise it. If the tribunal declines to do so, a party who proceeds with an application to the court would be in breach of the LCIA Rules, would risk its reputation with the tribunal, and would also potentially face the prospect of the court refusing the application influenced by the tribunal's decision, rather than the court conducting its own analysis consistent with the precise requirements of the law of the seat. In any event, a party seeking an urgent without notice freezing injunction against the respondent will find such an application completely undermined by any prior application it may be said it needs to make to the tribunal, on notice, for permission under Article 25.3 to apply to the court for such relief.

…the most pragmatic solution for parties concerned about this requirement is to include drafting in their arbitration agreement to dis-apply certain of the requirements of Article 23.2

Whilst anecdotal evidence from the LCIA suggests that a party may make a retrospective application for the tribunal's authorisation after it has sought the relief it needs from the court, the risk remains that a court could refuse to grant the relief on the basis that the arbitration agreement had not been complied with. Any suggestion of unilateral communications with the tribunal to obtain authorisation for an ex parte application would constitute a clear breach of the LCIA Rules and would risk prompting a challenge to the tribunal.

Until the LCIA issues guidance or revises its rules in the light of these considerations, the most pragmatic solution for parties concerned about this requirement is to include drafting in their arbitration agreement to dis-apply certain of the requirements of Article 25.3. For example, parties may choose to dis-apply the requirement for tribunal authorisation under Article 25.3, or they may also consider it prudent to dis-apply the requirement for the case to be "exceptional" in order to avoid any court having to contend with arguments that Article 25.3 imposes a higher or additional threshold of "exceptionalness" on top of any criteria, such as "urgency", imposed by the law of the seat.

Nor is this simply an LCIA Rules issue. Notably, a similar requirement for there to be "exceptional circumstances" is found in the SIAC Rules 2016. Other sets of institutional rules, such as the SCC Rules 2017, HKIAC Administered Arbitration Rules 2013, and ICDR Rules 2010 do not impose any additional hurdles, simply recognising that an application to a court is not inconsistent with an agreement to arbitrate. The ICC Rules 2017 specify that a party may apply to a court for interim relief after the file has been transmitted to the tribunal "in appropriate circumstances".

Given the significance of interim relief to the effective resolution of disputes through arbitration, and the ability to enforce arbitral awards, this is an area which merits attention from the parties at the transaction stage. As well as considering the powers of the potentially relevant courts to grant relief should the need arise, it is important to consider the requirements of the chosen institutional arbitration rules and how these two aspects of the dispute resolution process may need to work together. As ever, time spent reflecting on the scope of the dispute resolution provisions, and their suitability to the sorts of disputes that may later appear, can help the parties lay the groundwork to obtain effective interim relief in support of arbitration proceedings if it is ever needed.

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2025

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs