Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

Big data is rapidly changing the way in which regulators and law enforcement conduct an investigation and build a case. New technology reduces compliance costs, but also increases regulatory expectations of businesses' monitoring, detection and reporting capabilities. And, as technology evolves, monitoring for misconduct may soon involve predictive capability rather than merely detection. Meeting compliance expectations including due diligence on customers and suppliers, conducting internal investigations and managing government agencies during enforcement are all becoming more complex.

More than ever, companies need to keep up with the technology to keep up with their regulators in an investigation.

Regulators are already relying on advanced analytics and machine learning to spot suspicious patterns within and between data sets.

The US Securities and Exchange Commission deploys a "trader"-based approach to surveillance of financial markets for insider trading. Instead of examining trades occurring around the time of price movements in specific securities, the Commission identifies groups of individuals trading in a correlated manner.

Similarly, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, among others, are introducing artificial intelligence to review product disclosure statements to identify indicators of misleading statements during regulatory review.

As regulators' surveillance becomes more sophisticated, they also expect the regulated population to follow suit.

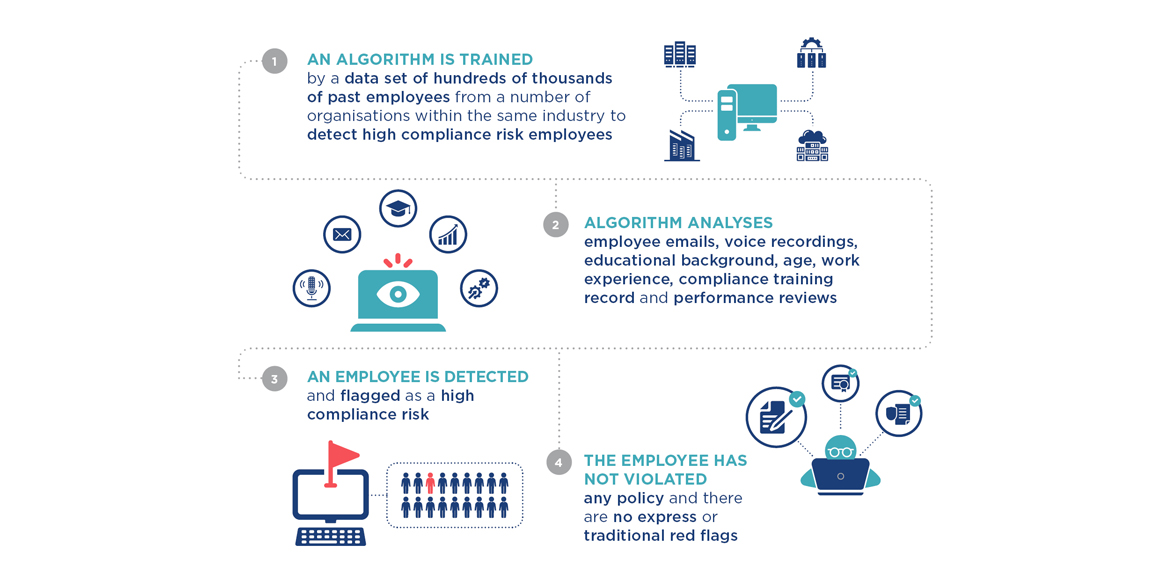

With advances in predictive analytics, one issue certain to arise is how to deal with a prediction of bad behaviour as opposed to evidence of bad behaviour.

Predictive analytics will certainly be a boon for the fight against misconduct. But its use will raise a number of practical legal challenges and questions when the technology is used to monitor employees or customers.

This raises a number of important questions for an employer in how should they use, share, record or report that information.

Perhaps increased monitoring would be required; should that person be given roles that entail a high degree of trust? Employers will need to rule whether and how this information is factored into promotion or remuneration decisions.

The employer will need to decide whether the employee should be told about their status, or whether any due process should be triggered by that categorisation.

They will also need to consider how that information should be used in an internal investigation. In highly regulated industries, it is important to decide what a regulator would expect you to do with this information. How will the regulator react if, despite the prediction, the employee does commit serious misconduct which the employer failed to prevent?

If that person is later investigated by government, law enforcement or a regulatory agency, should this information be volunteered?

Lastly, the risk of bias in the development and training of the algorithm should be considered. A number of algorithms have already been shown to carry an inherent risk of discrimination against protected classes of people.

Better data and analytics will improve third-party due diligence - spotting red flags that weren't previously possible and minimising false positives.

A decreasing reliance on staff to perform routine tasks will also free up time for higher order analysis and investigative work. This leads to more effective risk management at a lower cost.

However, as the capability of compliance functions increases, so too will regulatory expectations. 'More' and 'better' has been a constant theme in regulatory reform for some time, but how to set the standard for the use of technology in compliance is a new challenge.

One approach is to be technology neutral; a regulator does not pick a 'winner' by favouring a particular technology and thereby stifling innovation in the process. However, identifying what constitutes reasonable compliance measures is difficult in the abstract, given the broader range of technological solutions compared to more traditional manual or simple automated processes.

Government agencies and companies cooperating with law enforcement are changing the way matters are investigated and cases are built. The ability to produce an integrated view of evidence using multiple data sources is becoming more valuable.

For instance, the ability to spot red flags only apparent through a holistic review of voice recordings, texts, emails and financial records. Finding one smoking gun email on an employee's work account is becoming rare; cases more frequently rely on a reconstruction of events through multiple data sources.

The increasing use by businesses of cloud technology is also changing dawn raids and subpoena practice. The US and UK are leading the charge in developing a network of more extensive cross-border data request powers for law enforcement, to avoid delays in criminal investigations.

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs