Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

On 6 February 2020, Global Head of Contentious Construction and Infrastructure, Craig Shepherd, Head of Finance in Japan, Keith Gamble, and Dispute Resolution Associate, Victoria Green, delivered a seminar to members of the Overseas Construction Association of Japan on how to avoid joint venture disputes. In this month’s construction newsletter we offer a recap of the key takeaway points from that seminar, highlighting the issues for consideration when entering into a joint venture.

There are many different reasons why contractors may seek to enter a joint venture. In some cases this is simply a commercial decision, as it allows a contractor to share the risk and to increase its buying capacity, either with respect to a particular project, or more generally. In other circumstances, this is a necessity, where contractors with particular skills or experience need to seek partners with a different skill set in order to demonstrate the breadth of experience specified in tender documents, or where local law requirements specify that contracting entities must have a certain amount of local representation.

Regardless of the reasons contractors may have for entering a joint venture, they face similar choices in the establishment of their joint venture, and similar challenges in their operation. These are the issues we address below.

Once a contractor has identified a potential joint venture partner, the first question it will likely need to ask itself is how does it wish to structure the joint venture. Joint venture partners may elect to enter into a purely contractual relationship (i.e. without establishing a separate joint venture vehicle) or they may choose to set up a joint venture company in which each joint venture partner will be a shareholder.

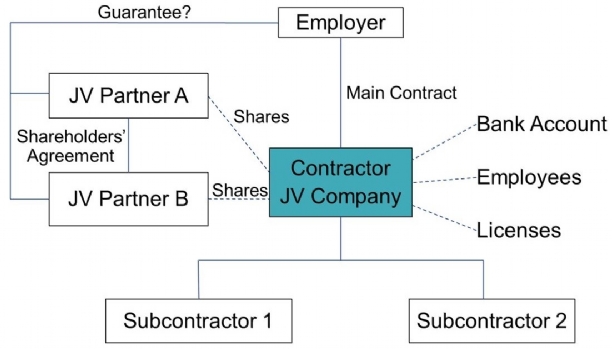

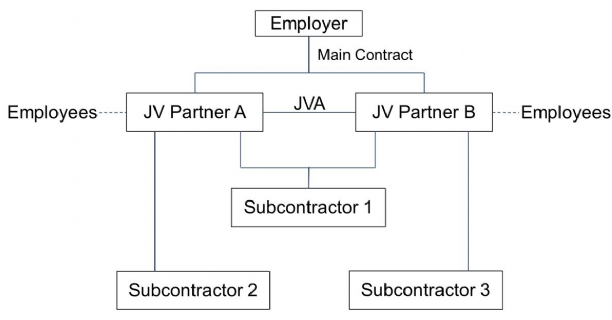

Whether or not a joint venture company is established impacts the whole contractual structure. If a company is set up, that company enters into the contracts, opens the bank accounts and does the work. It sits at the center of the structure. However, if there is no company, then it is for the joint venture partners themselves to step in, but they are likely to do so together for some things (such as both signing the main contract) and separately for other things (such as sub-contracts, which may be signed by only one joint venture partner).

Sample incorporated joint venture

Sample unincorporated joint venture

There is no single correct answer on how to structure a joint venture. Different joint venture structures will be appropriate in different circumstances. However, there are a number of factors which should be borne in mind when a contractor is considering its options.

Potential liability – One of the major reasons one may choose to incorporate a joint venture vehicle is so that the partners might benefit from limited liability. However, in most construction projects, an employer will require joint venture partners to provide a parent company guarantee for the joint venture company, particularly if this is a special purpose vehicle which has been incorporated for this project alone. As such, this effectively eliminates the benefit of limited liability associated with incorporating a joint venture entity.

Tax consequences – The tax implications of performing a project through an incorporated joint venture, as opposed to a purely contractual joint venture, will need to be borne in mind, in particular any potential risk of double taxation.

Administrative and operational concerns – The question of how assets and liabilities of the joint venture will be held may impact on the manner in which parties choose to structure their joint venture. For instance, as shown in the sample structure provided above, where a joint venture vehicle has been incorporated, we would normally expect this to directly employ relevant personnel and to hold the bank accounts, licenses and permits, and intellectual property in the design drawings. However, where no joint vehicle entity is incorporated, further thought will be need to be given to how each of these are held.

Intended duration – Where contractors only propose to enter into a joint venture for a single project, this may encourage parties to use a contractual joint venture. By contrast, if contractors intend to enter into long-term cooperation, it may be desirable to establish a joint venture vehicle.

Exit – If rapid exit from a failing joint venture is important, this may lead parties to favour a purely contractual joint venture, as, depending on the terms of the contract, it may be easier to exit this as there is no question of the need to wind-up a joint venture entity. However, the process of carrying on with a project when your partner defaults can be much easier if there is a company which you can control, rather than having to try to take over work being done in your partners’ name.

The form of the relevant contract will depend on the structure of the joint venture. (A joint venture agreement is typically used where a joint venture is unincorporated, whereas a shareholders’ agreement will be entered into where a joint venture vehicle has been incorporated.) However, there are a number of key provisions which are common to each of these agreements.

Participation / Cooperation

First, it is important to define the exact remit and purpose of the joint venture, establishing exactly what the partners are cooperating in relation to and what standard of cooperation and good faith (if any) is required of each partner.

Where the joint venture is unincorporated, it is also important to define which partner will take on the role of eader in the joint venture, what exactly this entails, and the extent to which the Leader shall be responsible to the other joint venture partners for actions undertaken in that capacity. Typically, there will be limits on the extent of the Leader’s liability to the other joint venture partners.

Finally, for unincorporated joint ventures, it is crucial to establish how the joint venture partners will share liability for any claim made by the Owner. For instance, will this be allocated to each of the joint venture partners on a pro rata basis in line with its participating interest, or should this be allocated on the basis of fault?

Finance

Another important consideration is financial arrangements, particularly: how bonds will be structured; how parent company guarantees will be structured (for instance, will these be provided for the entire project or only in proportion to participating interests in the project); and what will happen if a bond is called.

Control

The joint venture agreement or shareholders’ agreement should also define how control will be exercised; for instance, how the board of an incorporated joint venture, or any management board in an unincorporated joint venture, will be constituted; how decisions will be made; and what types of decision require a super-majority or unanimous consent.

Deadlock

Finally, particularly in a 50:50 joint venture, it is incredibly important to include provisions that attempt to avoid deadlock and provide a means of resolution if a deadlock does arise. These may include:

Although it is possible to minimize the risk of a dispute through clearly defining each party’s obligations and entitlements, it will never be possible to eliminate the risk of a dispute entirely. As such, we conclude this bulletin by reflecting briefly on how you might structure a claim against a joint venture partner.

Contractual claims

Where parties have properly recorded their joint venture, whether through a joint venture agreement or a shareholders’ agreement, a claim for breach of contract based upon that agreement will in almost all cases provide the easiest cause of action. The full range of usual remedies should be available for such a claim, including damages, specific performance and/or an injunction.

In principle, where the joint venture has been incorporated, it may also be possible in certain circumstances to pursue a claim against a joint venture partner for breach of the constitutional documents of that company. This is because in some legal systems the articles of association of a company act as a contract between a company (the joint venture vehicle) and its shareholders (the joint venture partners). However, this will depend on the law of the state in which the joint venture vehicle is incorporated and in a number of systems there are strict limits on when a claim can be pursued between shareholders on this basis. As such, these claims are relatively rare.

Alternative claims

A number of alternative statutory and common law claims may also be available where an incorporated joint venture is concerned and may be worth considering where a party lacks a contractual route of claim against its joint venture party. For instance:

Legal advice should always be sought before pursuing these to determine whether these routes of claim are available given the legal jurisdictions concerned in each case.

We hope that you have found this recap of the issues covered in our recent seminar of assistance. If you have any questions on any of the matters touched upon above, please do not hesitate to get in contact with one of our team.

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs