Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

Low commodity prices cause hardship for governments in resource rich countries, as much as they do for the businesses commercialising those resources.

This article briefly considers state responses to low oil prices. It goes on to consider how investors can allocate risk through their contractual provisions with host governments, suggesting negotiations with host governments and re-negotiation of contractual terms as a possibility. We also briefly set out how contractual rights may be enforced against the state, and some of the potential challenges associated with such enforcement.

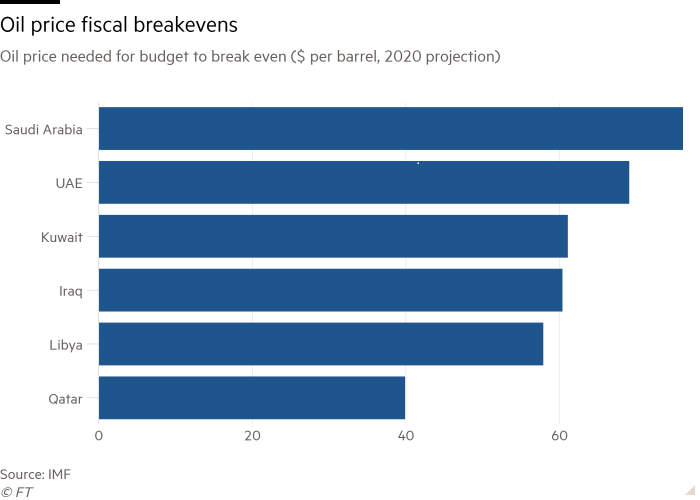

It is still too early to know how the latest slump in oil prices will affect governments in high oil producing countries who are also grappling with the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, what is clear already is that governments in the top oil producing countries are likely to be the hardest hit by the combined effects of low oil price and COVID-19. As seen in the graph below, the oil prices needed to balance the books in many major oil producing jurisdictions are substantially more than current oil prices.

Export earnings from oil and ancillary taxes is the main source of revenue for many oil producing countries and such countries plan their budgets based on long term oil price forecasts. The unforeseen crash in oil price will therefore mean that many oil producing countries will be forced to rework their budgets, slash spending and tap the debt markets. Further complicating matters is the fact that not all oil producing countries may be in position to access cheap credit.

In parallel, oil companies tasked and entrusted by these host states with extracting and commercialising resources are suffering from dramatic falls in valuations and need substantially to reconsider their strategies and operations to be resilient in the new reality.

The fall in oil prices and the consequent adverse financial effects as set out above may drive governments in oil producing countries to look closely at how they can extract more value from their natural resources such as oil in the short to medium term to tide them over the immediate crisis. We set out below certain contractual provisions which are likely to assume significance in the present context, as Governments and oil companies each try to weather this crisis to the best of their abilities.

Profit sharing and cost recovery: Production Sharing Contracts (“PSCs”) with states generally first allocate the hydrocarbons produced to the contractor to cover the costs of exploring, developing and operating under the contract. The remaining hydrocarbons are then divided as profit petroleum between the government and the contractor according to a pre-agreed percentage formula. In the current low oil price environment, investors should consider the specific terms of their PSCs and the mechanism for cost recovery and profit division. Some contracts include a limit on cost recovery as a percentage of production in any given year. In addition, some PSCs require a royalty to be paid to the host state government before cost recovery. Given that some governments may be eager to maximise short term revenues, we would expect to see a number of disputes around the recoverability of certain costs and, as a result, the allocation of ‘Profit Oil’ and revenues therefrom.

Tax: Along with profit sharing clauses and royalties, host states derive revenue from tax payments. While this is generally payable as income tax, host state agreements may provide for a different mechanism. Such tax clauses may be the subject of dispute or re-negotiation in the current climate with host governments seeking to relieve cashflow issues through increased tax revenues.

Production: Governments may make commitments to reduce oil production in the coming months. Such commitments are likely to affect international oil companies (“IOCs”) who may be required to reduce production in order for host governments to meet their commitments. If this is the case, parties will need to closely consider the applicable contractual arrangements around production rights and obligations.

Domestic Market Obligations: Foreign investor obligations in the domestic market can include, for example, requirement for producers to sell a specified portion of their oil or gas production at a rate equivalent to their export prices or at discounted rates to the domestic market. With already low oil prices, such obligations will place an increased burden on IOCs that are expected to sell at discounted rates in the domestic markets.

Insolvency: Licenses for hydrocarbon projects often have a termination right for economic distress or insolvency. With reduced cash flow, investors should consider whether they are likely to be affected by such provisions (or arguments to that effect).

Stabilisation clauses: Stabilisation clauses are a contractual protection against subsequent changes in the legal regime of your host country. While such clauses are generally included in oil and gas contracts, their specific terms differ. “Freezing clauses” have the effect of freezing the law applicable to the contract at the date of the contract. The more common type of stabilisation clause is an “economic equilibrium” clause, which is an agreement to adjust the economic terms of the contract on the occurrence of certain events. Such events generally include a change in the laws of the host state or a change in the way the law is applied. If triggered, such a clause will generally provide as a remedy an indemnity from the state, or a right to renegotiate the terms of the contract. A third, less common, type of stabilisation clause is an “intangibility clause”. It is an agreement not to terminate or amend the terms of the contract without consent of all parties. Stabilisation clauses may be triggered by legislative changes in response to the low oil price environment and COVID-19. A further driver for change in this area is the ambition to reduce reliance on fossil fuels in favour of cleaner energy sources. The low oil price may influence some of those ambitions for host states at least.

Contractual rights against the state can be enforced through either litigation or arbitration proceedings. There are certain issues to be mindful of when litigating or arbitrating against the state.

When enforcing contractual rights through arbitration, it is important to first consider whether the state is in fact a party to the arbitration agreement. Different jurisdictions have different rules on the ability of the state to enter into an arbitration agreement, particularly where the agreement relates to natural resources.

If the counterparty is in fact a state entity, a common challenge to a contractual claim is the defence of sovereign immunity. Sovereign immunity protects states from legal proceedings brought before the courts of a foreign jurisdiction and operates on two levels: (i) it can offer protection to a state or state-owned entity from legal proceedings before a court or arbitral tribunal (immunity from suit), and (ii) it can prevent the recognition/enforcement of a court judgment or arbitral award and execution against state-owned assets (immunity from execution). If the contract has expressly waived sovereign immunity in relation both to suit and execution, jurisdictional challenges on sovereign immunity grounds are less likely. Local law will, however, need to be considered.

If the relevant contract does not include an express waiver of immunity from suit and execution, contractor parties may face challenges in enforcing contractual rights against the state. In this instance, investment treaties may be relevant. If a relevant investment treaty is in place, this is likely to provide contractor parties with an additional level of protection. Claims under an investment treaty will be covered in the next episode of this series – ‘When a contract doesn’t cut it: reaching for the Treaty’.

State responses to the low oil prices are still evolving, and their impacts are likely to be seen in the coming months and years. This is a time for oil companies to review their contracts and assess how they can either collaborate with, or enforce contractual rights against, their host governments.

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs