Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

Key workers were on the front lines of Covid response across the globe. But can future cities support squeezed-out essential workers?

The contribution made by key workers to our cities has never been more essential – or more appreciated. Yet many of our cities are increasingly unaffordable for nurses, paramedics, teachers and police officers. The Covid‑19 pandemic may result in a renewed focus on enabling key workers to live and thrive in our cities, ensuring cities have access to a sufficient healthcare workforce when needed.

|

This article is part of our Future Cities Series where our experts explore the pressures facing our cities in the post-Covid era and map out the key issues and industry themes in re-thinking urban life. |

In many cities, key workers occupy a housing affordability gap. They earn too much to access social housing and rent assistance, but not enough to rely on the market alone. For shift workers, driving to work may be the safest option, so transport affordability is also a challenge. Moving to the outer suburbs and accepting a long commute may not be sustainable, so key workers look for work closer to where they live, or pivot towards higher-paying work. Over time, cities with a high cost of living face a net loss of key workers, while the demand for their services continues to grow.

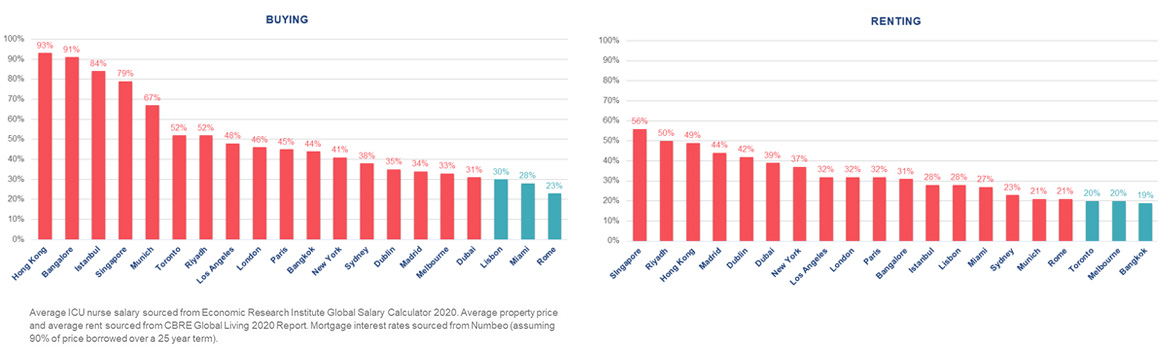

Key workers may experience housing stress where the cost of rent, or of servicing a mortgage, exceeds 30% of income. The graphs below show the percentage of average income for an ICU nurse which is spent on rent or mortgage payments across 20 global cities.

In many countries, housing affordability is a major political issue at a national and inter-generational level. As a result, housing affordability for key workers has become subsumed within the broader issue of housing affordability generally.

This is particularly evident in the UK. Between 2001 and 2004, a range of programs directed specifically at key workers (with both ownership and rental options) were put in place. The government’s current home ownership policies share some features with the earlier key worker schemes, but are open to anyone (subject to income tests). Key worker-specific programs tend to be localised and ad hoc, and are often more focussed on rental than on home ownership.

One learning from the pandemic is that cities should maintain a deployable, scalable, locally-based pandemic workforce. Priority roles include nurses (especially ICU-capable nurses), paramedics, medical technicians and contact tracers. Housing or tax incentives, or cash stipends, could be made available to suitably-skilled individuals who maintain pandemic training and can be called up if required (like a specialised army reserve).

While a ‘pandemic reserve’ is not directly aimed at addressing affordability, by giving these workers extra income or other incentives, their buying power is improved. In this way, the community can maintain as-needed access to workers who choose to pursue higher incomes eg in management roles.

Another likely post-pandemic trend is ‘de-casualisation’ of healthcare workforces. Predominantly casual workforces have been problematic during the pandemic, including due to increased risk where workers work at two or more facilities. Healthcare workers are facing significant risks, and demands for greater employment stability (and higher wages) should be expected as a result. In turn, this improves buying power.

KEY WORKERS AS A SAFE BETCompared to other occupation categories, key workers are more likely to maintain stable employment during a pandemic. The safe investment features of key worker housing are amplified when the economy is disrupted. If pandemic lockdowns become semi-regular events, the investment characteristics of key worker housing will diverge from other housing development projects, for example student housing. |

There are a number of existing and emerging models which seek to address housing affordability for key workers.

Despite the current focus on our key workers, it seems unlikely that housing affordability policy at a central government level will shift from affordability generally to key worker housing affordability specifically – including because key workers have been less hard hit, economically, than other occupation categories during the pandemic. If cities want to localise and future-proof their most essential workforce, innovative local solutions will be key. For developers, key worker-focused developments may be amongst the safest, most bankable projects (as well as being a social good) as we head into the new normal.

Subscribe to stay up-to-date with our Future Cities Latest Thinking: Australia-based contacts | Contacts based outside Australia

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs