Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

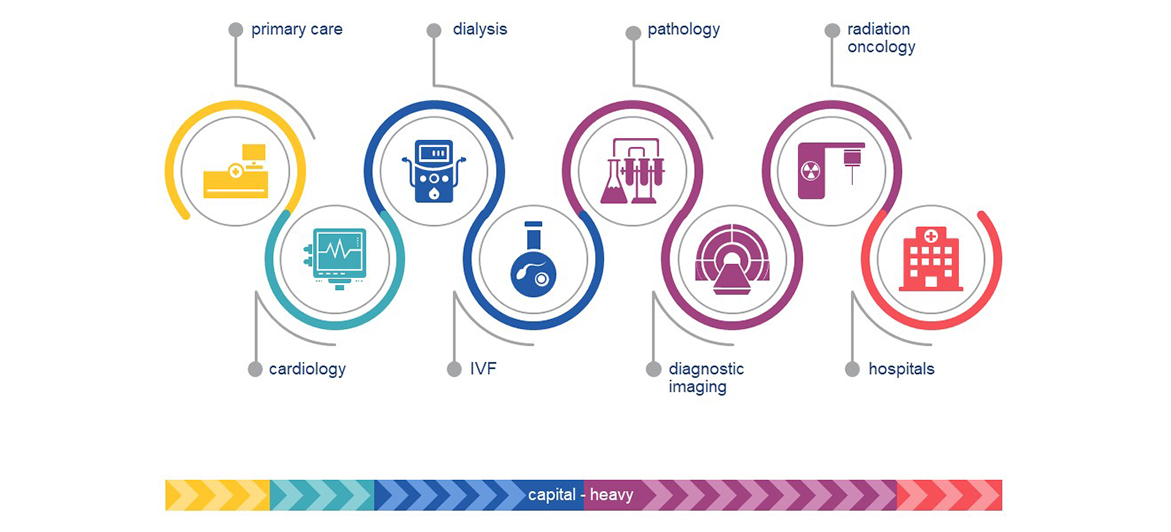

The search for yield is driving infrastructure investors to expand beyond typical core infrastructure assets into core+ or ‘infra-like’ assets. As part of this, infrastructure funds are increasingly looking at capital-heavy healthcare assets like hospitals and diagnostic imaging.

Healthcare assets exhibit many similar characteristics to core infrastructure assets, particularly if investors ‘think outside the box’ in relation to barriers to entry.

The willingness of infrastructure funds to look beyond core infrastucture assets is being driven by three factors.

Exposure to clinical risk, though insurable, has historically been a bridge too far for many infrastructure investors – even if the fundamentals of the asset are attractive.

Investment into a PPP or PFI structure is a long-standing option for infrastructure investors seeking exposure to the healthcare sector. Traditional PPPs include financing, design, construction, hard FM and sometimes soft FM such as security and porterage – but not clinical services (hence ‘no blood’). Recently though, infrastructure investors have been more willing to move further into the value chain, investing in operating businesses which perform clinical services.

HOW MUCH CLINICAL RISK IS IN THE STRUCTURE?Healthcare businesses may be structured to carry less clinical risk. For example:

|

A basic characteristic of an infrastructure asset is that it provides an essential service. In many developed countries, private healthcare services operate alongside a free or subsidised public healthcare system. Is private healthcare a luxury or a necessity in these countries?

While individual consumer decisions may treat private healthcare as a discretional spend in a mixed system, at a policy level, the government comes to depend upon the private system servicing a stable proportion of demand. If a major private operator fails or exits a region or service, the demand diverts back to the public healthcare system - and healthcare demand can’t wait for long. Since the government would pay for market failure, it will logically be willing to support policy settings which prevent market failure. As an example of this, during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Australian Government provided cost coverage for all Australian private hospitals.

Barriers to entry are another characteristic of infrastructure assets. Because they confer an advantage on incumbents, barriers to entry de-risk investments in existing businesses.

High risk healthcare services such as running a hospital or dealing with radiation apparatus will always require a licence (the position varies for lower risk activities like primary care clinics). However, merely needing a licence is not a significant barrier to entry where the licence is obtainable by anyone who is capable of meeting the applicable standards. Some jurisdictions also have direct barriers to entry – for example, the government will not grant new private hospital licences or allow existing facilities to expand unless it considers that there is unmet demand in the market. Direct barriers to entry can also arise as a result of government seeking to control its spend on healthcare services – for example, where there is a finite number of funded ‘beds’ in a city or region at any one time.

But healthcare also has other – in some cases unique – barriers to entry which favour incumbents.

Viewed as a business asset, relationships with doctors have strong protective characteristics. Fully qualified doctors, especially medical specialists:

These features mean that established operators with strong relationships with a group of doctors have a significant advantage over new market entrants.

Healthcare businesses need to meet accreditation standards and get quality right from day one, regardless of whether demand takes time to build. If the business undertakes higher risk procedures, capacity to handle contingencies and complications must be available, regardless of whether the facility has few or many patients. Lower demand may not enable lower costs.

Scaled operators are better able to manage a staged ramp-up and to achieve sufficient occupancy quickly. They can share resources with and refer patients from other facilities. Their existing reputation and relationships should mean that demand grows more quickly than for a new entrant.

THE ‘MULTIPLIER EFFECT’ OF HIGHER ACUITY SERVICESIf a hospital wants to offer maternity services, it will also need to have a range of supporting services available at all times (regardless of how busy the maternity ward is).  |

In jurisdictions where funds flow through contracts with government or insurers rather than directly from consumers, securing contracts with funders is key to revenue and operates as a barrier to entry. In healthcare, funders are attracted by reputation, service mix and location. Price competition tends to favour incumbents as it can be challenging to achieve efficiencies safely. Even where contracts with funders are ostensibly short-term, the reality is that incumbent providers tend to have their contracts extended (assuming satisfactory performance) because service provision cannot be interrupted and switching providers would be highly disruptive.

The data held by healthcare businesses is increasingly viewed as a valuable asset in its own right. Patients are likely to return to providers who already hold the patient’s health information (or can quickly obtain it). Bulk data and data analytics are essential to enable providers to translate population demographics into demand profiles to inform their investment decisions and to price services for contracts with funders. New entrants are therefore disadvantaged by their lack of healthcare data.

A further feature of infrastructure assets which is found in healthcare businesses is inelastic demand. Both individuals and governments tend to prioritise their healthcare spend over other expenditure during economic downturns – no doubt in part because most healthcare expenditure can only be delayed, not avoided (and may increase if delayed – as with cancer screening compared to cancer treatment). In systems with government subsidisation or high insurance penetration, healthcare services may lack price signals for consumers, so spend is not affected by consumer confidence. Healthcare demand is often irrational – both individuals and governments will pay for treatments with a relatively-low success rate and attempts by government to de-fund such services are often politically divisive.

The healthcare sector has long been a favourite asset class for private equity and some healthcare businesses are now in the hands of their second or third private equity investor, with doctors who work in the business also holding a stake. A 3-5 year investment horizon can be disruptive for healthcare businesses which need to take a long term view on value generation (for example through the training of registrars). A tension arises where the main value realisation opportunity is an exit event, but a buyer or investor in an IPO would want the doctors to stay on as shareholders to maintain an alignment of interest. Sale to an infrastructure investor, with a longer term investment horizon and a focus on dividends, offers an alternative path for healthcare businesses with the right characteristics.

We expect the ‘infra-like’ trend to accelerate, not only in healthcare but in other infrastructure adjacent assets like data centres, renewable energy projects and digital fibre networks. There is capital to deploy, and the healthcare sector has emerged strongly from the pandemic. Possibly the most exciting feature of this trend is the potential for an alignment between investors and doctors in growing long term value while delivering services which benefit society.

Herbert Smith Freehills has market-leading experience acting for infrastructure funds investing in healthcare businesses including recently acting for:

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs