Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

The prospect of an independent Scotland raises a number of significant questions as to the impact on the rights and obligations of both Scotland and the rest of the UK (rUK) under international law. This short article highlights some of the key international law implications of Scottish independence and how they may impact on private parties, including in relation to Scotland’s rights and obligations under treaties, membership of international organisations and the question of how the maritime and land boundaries between the rUK and Scotland would be delimited.

There is no clear rule as a matter of international law regarding the consequences of one State splitting off, or seceding, from another. Three main theories exist in the circumstances of Scottish independence:

The first of these three is the most likely outcome, namely that rUK will continue to exercise the rights, obligations and powers under international law as the UK did previously (known under international law as the continuing State), while Scotland emerges as a new State (known as a successor State).

The reaction of the international community to this question will be also be influential, and will be informed by historical precedent. When the USSR broke up, Russia declared that it was the continuation of the USSR and this was widely accepted by the international community. In contrast, on the break-up of Yugoslavia, Serbia similarly claimed that it was the continuation of Yugoslavia (together with Montenegro under its former name "the Former Republic of Yugoslavia", or “FRY”). However, this was not accepted by most third States or by other former Yugoslav States, and the United Nations declared that the FRY would have to apply anew for UN membership. When Czechoslovakia broke up into Czech Republic and Slovakia, even though Czech Republic was the larger by geography and population, it did not claim continuity. Both countries confirmed that they would comply with all pre-existing obligations and be bound by all treaties, including bilateral treaties, and there were no objections from other States. In the case of the UK, however, with 92% of the population, two-thirds of the territory and the main government institutions, it seems unlikely that any State would dispute rUK’s claim to be the continuing State.

The significance of this issue lies in whether an independent Scotland will remain party to treaties, and a member of international organisations established by treaties, to which the UK is party. Treaties of course create rights and obligations in connection with a very broad range of issues, including boundary delimitation, human rights, environmental compliance, trade, transport, taxation, investment, and civil, criminal and judicial cooperation.

Based on principles identified through State practice, the position for Scotland as a new State is likely to be as follows:

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) was ratified by the UK in 1951. The ECHR contains a comprehensive regime for the protection of rights and freedoms, including the right to life, freedom of expression and assembly, fair trial, and respect for private and family life. Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 of the ECHR enshrines rights relating to the protection of property.

It is likely that the ECHR would continue to apply to Scotland, even as a new State. In the 2009 case of Bijelic v Montenegro and Serbia, the European Court of Human Rights held that the ECHR and Protocol No. 1 remained in force over the territory of a successor State at all times despite independence. This was on the basis that the fundamental rights protected by human rights treaties belong to the individuals living in the State concerned, “notwithstanding its subsequent dissolution or succession”.

However, Scotland would need to seek membership of the Council of Europe. The Committee of Ministers of the Council has the power under Articles 4 and 16 of the Statute of the Council of Europe to invite a State to join.

If the UK had still been a member of the EU at the point of Scottish independence then it would have been the continuing rUK that retained the EU membership and Scotland would have had to apply to join the EU using the standard legal process set out in Article 49 of the Treaty on European Union. So now that the UK has left the EU, Scotland’s position is not dissimilar. Scotland was an EU member (as part of the UK) for 47 years and continues to adhere to a considerable body of EU law under sections 2 to 4 of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. However, and in any case, Scotland must still meet the accession criteria, or Copenhagen criteria (as defined by the European Council in Copenhagen in 1993) to join the EU. There are three pillars to the criteria:

An application for EU membership would also raise other questions such as whether Scotland would be required to join the Schengen system and the Euro. For a more detailed discussion of the implications of Scotland joining the EU, see Scottish independence and EU membership: process and implications.

The location of any future land and maritime boundary between rUK and Scotland is clearly a significant issue, given the intrinsic relationship between territory and national identity, and also in view of sovereign rights over natural resources such as existing and potential oil and gas fields, and offshore wind, wave, tidal and Carbon Capture Usage and Storage (CCUS) projects.

The land boundary between Scotland and England was established in the 1237 Treaty of York. While some borderlands were disputed during the following two centuries it is one of the oldest existing borders in the world.

In the event of Scottish independence, it would be necessary to agree the maritime boundaries between Scotland and rUK. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) sets down the approach to delimitation of maritime boundaries between adjacent coastal States. First, the two States should seek to agree the boundary. If agreement cannot be reached, UNCLOS provides for a dispute settlement procedure whereby the dispute can be determined by a tribunal or by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) subject to the election of the parties. International law has developed in this area to a point where there are clear principles that will be applied. There are three key steps:

Pending any agreement as to delimitation, UNCLOS provides that States must “make every effort to enter into provisional arrangements of a practical nature and, during this transitional period, not to jeopardise or hamper the reaching of the final agreement. Such arrangements shall be without prejudice to the final delimitation”. As a practical matter therefore, rUK and Scotland should be able to reach temporary agreements (such as establishment of a joint development zone) to facilitate (continued) investment in, and exploitation of, natural resources in territory yet to be finally delimited.

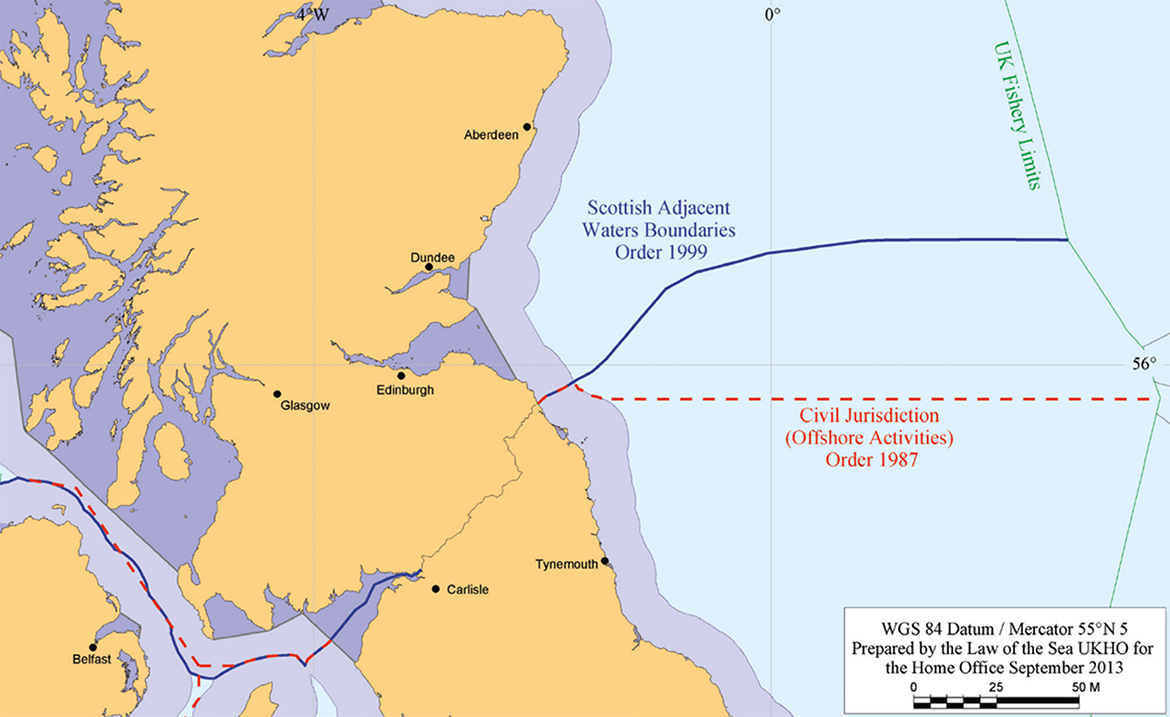

The discussions between rUK and Scotland concerning the maritime boundary are likely to focus on issues highlighted by the above map (published in 2014 as part of the UK Government’s analysis in the context of the previous Scottish independence referendum):

The area between these two lines is substantial (about 5,500 square nautical miles), and contains a number of existing oil and gas fields. These fields are of course significant in terms of their exploitation, but also due to the obligations in connection with their eventual decommissioning.

The international law issues arising in the event of Scottish independence may take time to resolve but established principles exist to guide the forward process. These issues underpin a number of other key considerations of direct concern to businesses and individuals which are covered in more detail in our other briefings found here.

Partner, Global Co-Head of International Arbitration and of Public International Law, London

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs