Litigation over designs is relatively uncommon in Australia.

Nevertheless, the designs scheme can be effectively utilised by designers to enforce their monopoly rights against competitors who wish to enter the market. A recent Federal Court decision regarding the infringement of a registered design for a microphone handset for a mobile radio product demonstrates that designs can be valuable intellectual property assets and provides useful guidance to designers and manufacturers as to the how the Court approaches the question of assessing design infringement.

Key takeaways

- The value of registered designs. Registered designs can be effectively used to enforce commercial interests. The injunction granted by the Court restrains Uniden from entering the Australian market with its XTRAK product while the GME design remains registered. This case serves as a reminder to designers and manufacturers as to the importance of registered design rights.

- Assessing infringement of registered designs. In determining infringement, in addition to noting the similarities and differences between the designs in question, the Court will consider the state of development of relevant prior art designs and the freedom of the creator to innovate having regard to any functional limitations which may exist. The Court will undertake this assessment by standing in the shoes of the “informed user” who is a notional person taken to be familiar with products embodying the designs in question.

- Efficiency of intellectual property litigation. This case was filed and heard with a judgment issued within two months. It demonstrates that in appropriate cases, and where the parties are able to cooperate to narrow the scope of issues in contest, the Court is able to move quickly to finally determine intellectual property proceedings.

Overview of the designs scheme in Australia

Designs in Australia are protected under the Designs Act 2003 (Cth) (the Act). A “design” is defined, in relation to a product, to mean “the overall appearance of the product resulting from one or more visual features of the product”. A “visual feature” is defined to include the shape, configuration, pattern, orientation and ornamentation of the product, but does not include the feel or material used in the product.

For a design to be registrable, it must be “new” and “distinctive” when compared to other designs existing at the time (the “prior art base”). A design is considered new unless it is identical to another design within the prior art base. Similarly, a design is taken to be distinctive unless it is substantially similar in overall impression to a design forming part of the prior art base.

The owner of a registered design is granted various exclusive rights by the Act, including the right to make, import and sell products which embody the registered design.

The process for registering a design with IP Australia is relatively straightforward because applications are assessed mostly for compliance with the formalities of the legislation. However, in order to enforce a registered design, the design must first be substantively examined and certified. During that process IP Australia will assess whether the registered design meets the criteria for registrability, including whether the design is “new” and “distinctive” when comparted to the prior art base. Only once a registered design has been examined and certified can the registered owner, or an exclusive licensee, commence Court proceedings for infringement.

A person infringes a registered design if they make, import or sell a product which embodies a design that is identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to, the registered design. In determining this question, regard is given to:

- the state of development of the prior art base for the design;

- particular visual features identified in the design application as being new and distinctive;

- the amount, quality and importance of parts of the design that are substantially similar to the other design; and

- the freedom of the creator of the design to innovate.

In applying these considerations, the Court puts itself in the shoes of the “informed user”, a notional person who is familiar with the products to which the design relates, or similar products. Importantly, in determining this question, more weight is given to the similarities between the designs than to the differences between them.

If infringement is proved, the Court may grant relief including injunctions as well as, at the election of the owner of the design, either damages or an account of profits.

GME Pty Ltd v Uniden Australia Pty Ltd

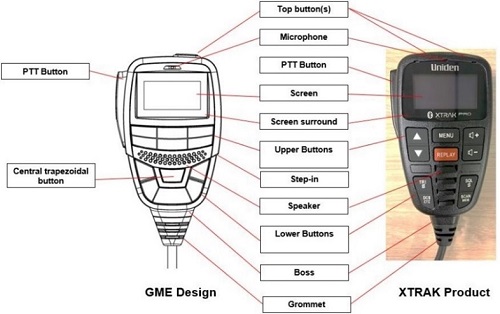

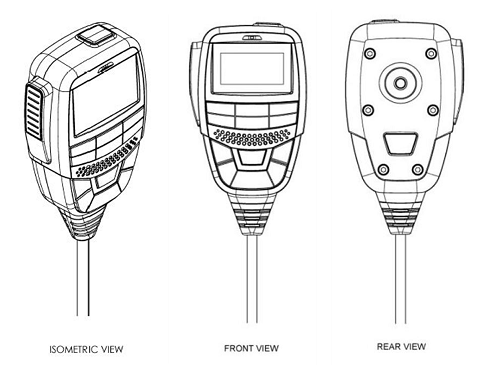

In GME Pty Ltd v Uniden Australia Pty Ltd1 the applicant (GME) was the owner of a design for a microphone (GME design) depicted below.

GME commenced proceedings against the respondent (Uniden) alleging that it threatened to infringe the GME design by the imminent launch of its XTRAK UHF mobile radio product in Australia. The XTRAK product is shown below.

The decision

The Court found in GME’s favour, holding that the XTRAK product embodied a design that was substantially similar in overall impression to the GME design. The Court granted an injunction in favour of GME restraining Uniden from infringing the GME design – including by making, importing or selling the XTRAK product in Australia – without the licence or consent of GME.

The judgment provides useful guidance as to the approach the Court takes when assessing whether two designs are substantially similar in overall impression for the purposes of determining registered design infringement.

The focus of the comparison is on the overall impression created by the two designs

Whilst noting that the relevant comparison is essentially impressionistic, the Court noted that the comparison is not done “by ignoring matters of detail, but by assessing the impact of particular visual features, including any matters of detail, on the overall impression created by each of the two designs”. The Court quoted previous authority that this approach involves a “studied comparison” between the two designs, a test quite different to the assessment of “deceptive similarity” in trade mark law which takes into account a person’s “imperfect recollection”.

In determining that the designs were similar in overall impression, the Court conducted a close analysis of the features of the two designs. When it came to qualitatively assessing the overall impression conveyed by the two designs, the Court found that the similarities between the GME design and the XTRAK product – including the outer silhouettes, the shape and position of the PTT button, the shape and positions of the screen and the upper buttons – outweighed the differences – including the position and layout of the lower buttons and the presence of the speaker grille in the GME design. A side-by-side comparison of the visual features which was reproduced in the judgment is depicted below.

The relevance of the prior art base to assessing infringement

The prior art base in registered designs cases is directly relevant to both questions of infringement and validity. If the registered design shares a number of common visual features with the prior art such that it does not constitute a great advance over prior art designs, the Court will be less likely to find that another product infringes by virtue of sharing those same features (also belonging to the prior art). This means that in an infringement case, consideration will be given to the visual features of the relevant prior art designs to inform an assessment of the significance of the similarities and differences between the registered design and the alleged infringing product.

After reviewing the prior art designs relied upon by the parties, the Court observed that although there were a number of features common to all prior microphones, there remained considerable scope for variability within the characteristics of their designs. Having regard to this, the Court determined that the XTRAK product was more similar in overall impression to the GME design than any of the prior art devices relied upon.

Functional aspects of designs and freedom to innovate

The Court is also to have regard to the “freedom of the creator of the design to innovate” when assessing infringement. If designers are limited in their ability to innovate due to functional limitations specific to the product, this will be taken into account in the Court’s assessment of whether the similarities between designs lead to a finding of infringement.

In the present case, the Court considered the functional limitations of handheld radio microphones and noted several features, identified in the expert evidence and the prior art designs relied upon by the parties, which are necessary to include in any design of such a microphone. However, the Court rejected Uniden’s argument that these functional limitations “drive the design” of such products, and instead found that there remained freedom for creators to innovate in the design of handheld radio microphones.

- [2022] FCA 520.

Find a lawyer

Legal Notice

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024

Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs