Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

A much-anticipated UK decision confirms directors' obligations to creditors, but changes little in practice

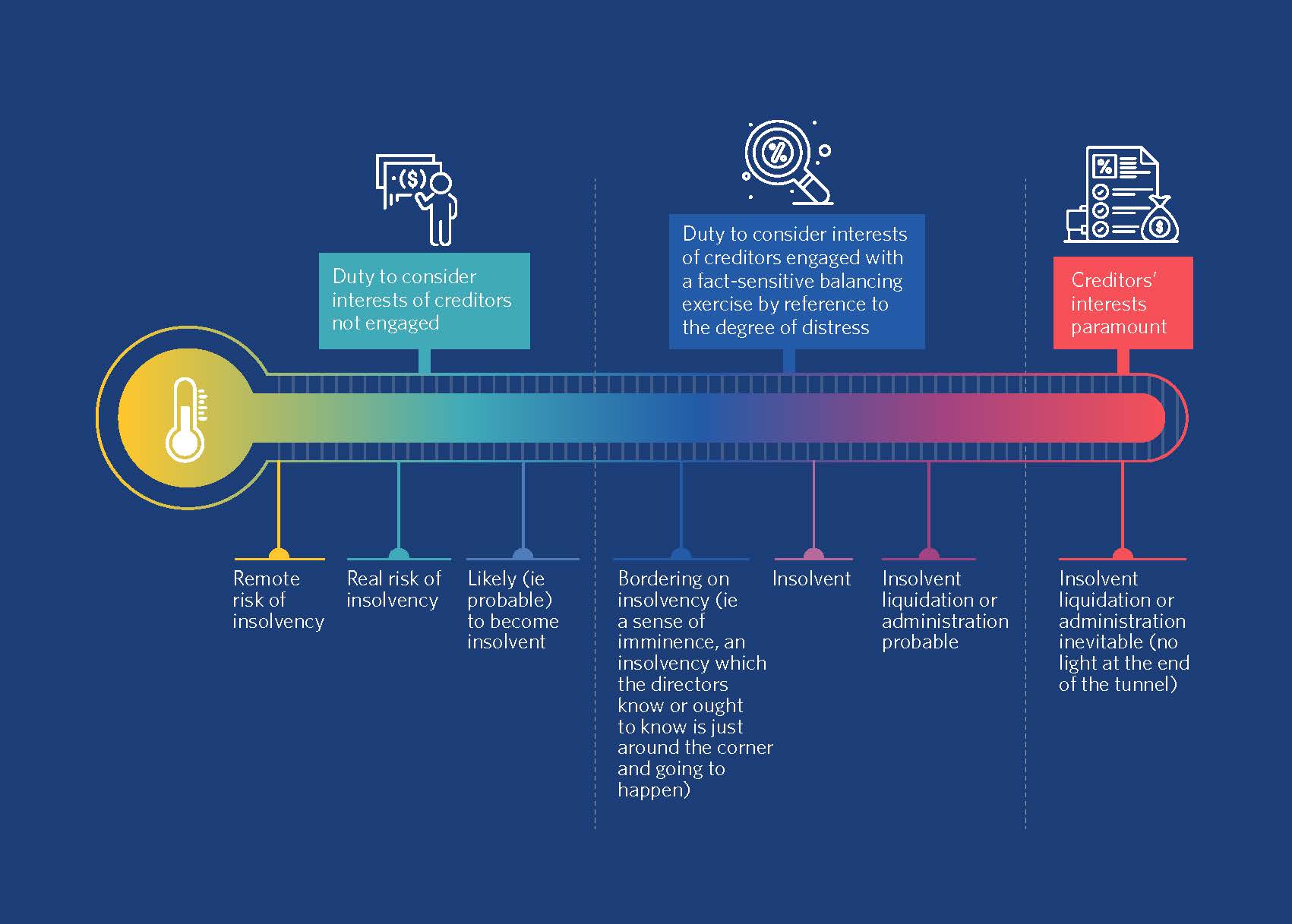

When directors should consider the interests of creditors is ultimately a judgment call which is only truly scrutinised in the sometimes harsh light of 20/20 hindsight in a subsequent administration or liquidation. So best practice for boards of stressed English companies is to manage the risks to directors by considering creditors' interests too soon (rather than too late). When boards consider the potentially different interests of creditors and shareholders early, it is also often the case that there is substantial alignment. Plus, having been through this exercise helps a board to formulate sensible and prudent contingency planning by identifying points in the future where interests may diverge.

Since March 2019, firms across the City have referred to the test used by Lord Justice David Richards in the Court of Appeal in BTI v Sequana that creditors' interests are engaged when it is likely (meaning probable) that a company will become insolvent. The majority in the Supreme Court has now:

Here, the decision is likely to mean little practical change for boards of stressed businesses following existing best practice. There may be scenarios where there is a practical difference between the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal tests. These are however likely to be rare. As before:

Sometimes, momentous decisions are most important for what they do not do. Directors can take some comfort that the Supreme Court has declined to hold that the duty to have regard to creditors' interests is engaged where there is only a risk of insolvency – since doing so would have increased the scope for potential personal liabilities where companies encounter distress.

We previously considered the background to this case here in the context of the Court of Appeal's ruling in these proceedings in early 2019. However, broadly, and as set out in the Supreme Court's judgment:

As set out in our previous briefing, the Court of Appeal dismissed BTI's appeal.

Delivering an extensive judgment following a thorough review of the authorities, Lord Justice David Richards (as he was then) posited four potential points in time at which the duty that directors owe to the company to have regard to creditors' interests (otherwise referred to as the "creditor duty") could in principle be engaged: (1) upon actual insolvency; (2) upon imminent insolvency ("on the verge of insolvency" or "near-insolvent"); (3) where insolvency is more likely than not ("likely to become insolvent" or "of doubtful solvency"); and (4) where there is a realistic prospect of insolvency ("as opposed to a remote risk").

Preferring the third of these tests, David Richard LJ concluded that the creditor duty is engaged when the directors know or should know that the company is or is likely to become insolvent, with "likely" meaning probable.

As such, since it could not be said that AWA was likely to become insolvent at the time it paid the dividend to Sequana in May 2009, the directors were not in breach of the creditor duty – that duty was never engaged. Notably, the Court of Appeal left open, for these purposes, whether, once the duty is engaged, creditors' interests are paramount or are merely one factor to be considered without being decisive.

BTI obtained leave to appeal to the Supreme Court.

Before a Supreme Court made up of five sitting justices, Lords Reed, Hodge, Briggs and Kitchin and Lady Arden, the appellant, BTI, argued that the Court of Appeal had erred in its conclusion as to the applicable test for when the creditor duty is engaged. The appellant argued that a "real risk" of insolvency is sufficient to engage that duty.

The respondent directors, on the other hand, argued that the Court of Appeal was wrong to conclude: (a) that a creditor duty existed at all; and (b) that, if it did, that duty (i) could apply to a dividend which was otherwise lawful; or (ii) could be engaged short of actual, or possibly imminent insolvency. In the alternative, the directors argued that the Court of Appeal was right to hold that a real risk of insolvency, falling short of a probability, would not engage the creditor duty.

There were therefore four issues before the Supreme Court:

The Supreme Court justices were unanimous in their dismissal of BTI's appeal on the grounds that, although a duty to consider the interests of creditors does indeed exist, a "real risk" of insolvency is not sufficient.

On the contrary (in the majority's view) the creditor duty is only engaged when the directors know, or ought to know, that the company is insolvent or bordering on insolvency, or that an insolvent liquidation or administration is probable.

We summarise below the Supreme Court's findings on each of the four questions before it:

(1) Is there a common law creditor duty at all?

Under section 172(1) of the Companies Act 2006, directors are required to act in a way which they consider, in good faith, would be most likely to promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members as a whole. It codified the long-established common law fiduciary duty to act in good faith in the best interests of company, implementing the recommendations of the Company Law Review Steering Group ("CLRSG") (an independent review body established in 1998 to make recommendations for the reform of company law).

According to Lord Reed (with whom the other justices agreed), although commonly referred to as the "creditor duty", there is in fact no duty owed to creditors, or any duty separate from the directors' fiduciary duty to the company. As to this, Lady Arden observed that there exists no rule of law which entitles creditors, either directly or derivatively though the company, to sue the directors if they do not comply with the creditor duty: "In fact, the creditors can neither sue for a breach of it nor recover any losses that ensue for breach. The remedies are those for a breach of the duty under section 172(1). Accordingly, any financial award resulting from a breach of the obligations owed in relation to creditors would inure for the benefit of the company, not for the creditors who were harmed by the breach..."

As Lord Reed went on to explain, there is a rule which modifies the ordinary position under section 172(1) such that, when it applies, the company's interests for the purposes of that section are to be taken to include the interests of its creditors as a whole.

The justification for this finding of the existence of the creditor duty was essentially threefold:

Notably, all justices agreed that the shareholder authorisation or ratification principle (namely, that outside of insolvency, the shareholders are entitled to authorise or subsequently ratify the conduct of the directors) does not prevent the recognition of the creditor duty. Where the directors are under a duty to act in good faith in the interests of the creditors, the shareholders cannot authorise or ratify a transaction which is in breach of that duty. This is because there can be no shareholder ratification of a transaction entered into when the company is insolvent, or which would render the company insolvent. The Court also held that there is no conflict between the creditor duty and section 214 of the Insolvency Act 1986, which deals with wrongful trading and only applies in circumstances where the director knew or ought to have concluded that there was no reasonable prospect that the company would avoid insolvent liquidation (per section 214(2)(b)). Indeed, in the view of Lord Hodge, "there may be more egregious circumstances in which the absence of a remedy beyond section 214 would appear to be a lacuna in our law".

(2) When is the creditor duty engaged?

As noted above, the majority held that the creditor duty is engaged where the directors know or ought to know that the company is insolvent or bordering on insolvency, or that an insolvent liquidation or administration is probable.

As Lord Briggs explained, the idea that a real risk of insolvency is an appropriate trigger for the creditor duty "rests upon an unsound principle" – namely, "it assumes that creditors of a limited company are always among its stakeholders, so that once the security of their stake in the company (i.e. their expectation of being repaid in full) is seen to be at real risk, there arises a duty of the directors to protect them…The true principle by contrast is that creditors (or at least unsecured creditors) are not the main stakeholders in the company at any earlier date than when it goes into insolvent liquidation".

Although Lord Reed and Lady Arden agreed with the majority's characterisation of the relevant threshold, they were prepared to leave open the question of whether knowledge on the part of the directors is an essential element of the test. In the event, that question did not arise on the facts since it was clear that AWA had not met the relevant threshold.

In terms of what is meant by the word "insolvency" for the purposes of the foregoing test, it was accepted that the Court had heard no submissions on this point. However, Lord Reed was of the view that it means balance sheet and/or cash flow (or commercial) insolvency. There is also scope for argument following comments of Lady Arden and (potentially) Lord Briggs that "insolvency" for these purposes excludes what is referred to as a form of "temporary commercial insolvency" (giving the example of what directors may consider to be a temporary cash-flow shortage as the result of an unexpected event, like the covid-19 pandemic).

(3) What is the content of the creditor duty?

Although the content of the creditor duty did not need to be determined because, on the facts, it was held not to have been engaged, the following principles (albeit obiter) emerge from the Supreme Court's consideration of that content:

(4) Can the creditor duty apply to a decision by directors to pay a lawful dividend?

Again, this question did not need to be determined since the creditor duty was found not to have been engaged. However, the Supreme Court noted that, in principle, the creditor duty can apply to a decision by directors to pay a dividend which is otherwise lawful, for two reasons:

The latest formulation of the test set out by the Supreme Court will see an amendment to model forms in many law firms across the City – and has already seen a considerable amount of electronic ink spilt on LinkedIn.

Directors can take comfort that the Supreme Court recognises the inherent risk taken by creditors of limited liability companies and has not sought to protect creditors by extending directors' personal liability to an earlier point in time (i.e. where there is only a mere risk of insolvency). In this sense, the decision is likely most significant for the submissions it rejected.

Directors' judgment calls however remain difficult where they are required to assess where on the "sliding scale" of insolvency the company is presently positioned so as to determine where the balance of competing interests between the company's various stakeholders should lie. As Lady Arden noted in her judgment: "the progress towards insolvency may not be linear and may occur not as a result of incremental developments but as a result of something outside the company which has a sudden and major impact on it." Indeed, despite best-laid plans, directors may still face significant challenges when it comes to identifying and responding promptly and effectively to circumstances which may threaten the existence of the company so as to minimise the risk of personal liability. But at the very least, the Supreme Court has declined to increase the load on directors in those circumstances.

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs