In this article, we explore the potential implications of the Australian Human Rights Commission’s recent report on Human Rights and Technology (the Report). Released in May 2021, the Report contains 38 ambitious recommendations which may have far-reaching consequences for companies’ use of AI decision making tools.

Beyond its specific recommendations, the Report also reflects a broader trend in Australia towards:

- articulating how existing legal frameworks can be applied more effectively to new technology – in this case, how Australia’s current human rights protections have a role to play in regulating the development and use of AI; and

- increased regulation of automated and algorithmic technologies through the introduction of new legal obligations which aim to make those technologies more transparent and comprehensible.

It follows the Federal Government’s introduction of the News Media Bargaining Code earlier this year, which imposed new requirements on designated digital platform services to disclose certain data to news businesses and notify them of significant changes to algorithms, and a broader Commonwealth regulatory focus on digital platform regulation and algorithm transparency.

These developments suggest tech companies will soon be grappling with overlapping and complex regulatory regimes, directed at solving diverse policy concerns that arise from emerging technologies.

The Federal Government will soon consider the Report, as announced in its recently released AI Action Plan which we discuss here.

KEY TAKEAWAYS AND IMPLICATIONS

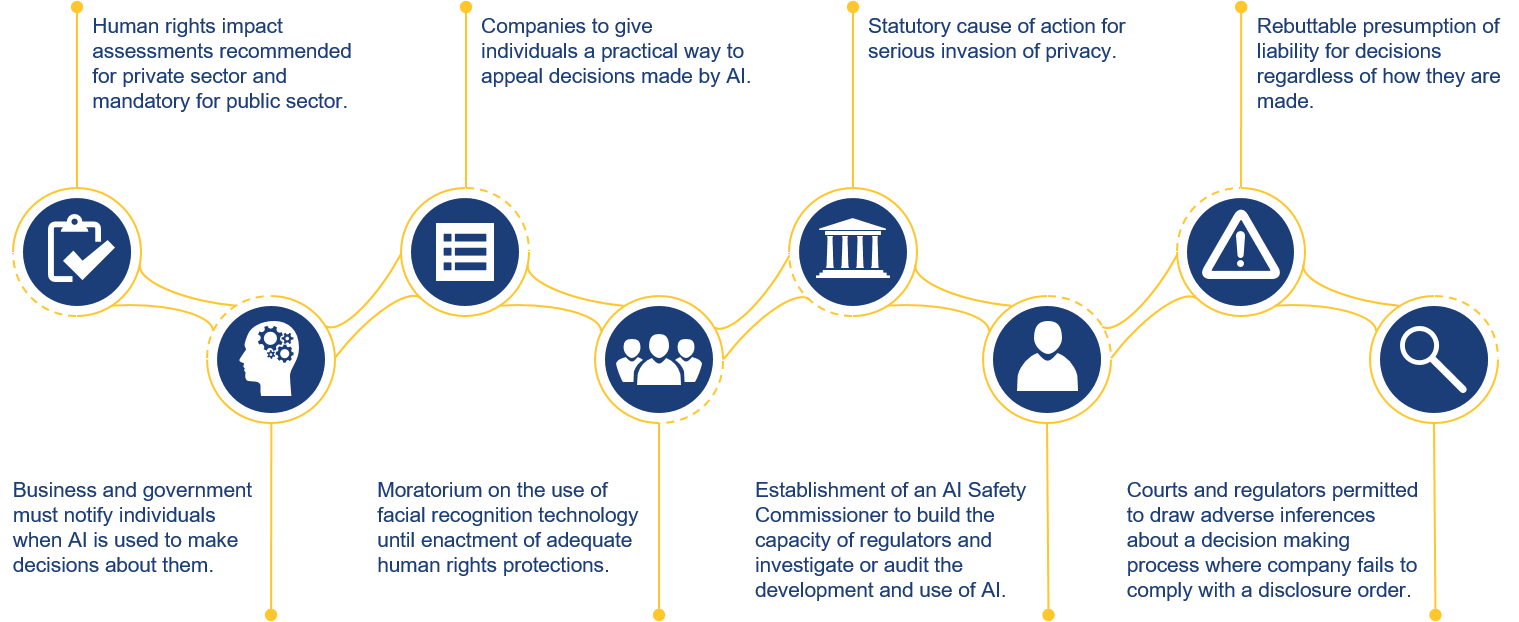

Key recommendations with implications for the private sector:

Our practical guidance for companies:

AI design and development

- Consider suitability of AI decision tools in high risk areas. In light of the proposed rebuttable presumption that companies are liable for decisions (including automated or AI decisions) regardless of how they are made, companies should evaluate and seek advice on the risks of using AI decision-making in high risk areas or which may result in unlawful discrimination (for example, use of AI-assisted employment tools to assess the suitability of job candidates, where decisions could be based on protected attributes such as age, disability or race).

- Consider human rights issues at key stages. In line with the Report’s recommendation to implement human rights impact assessments, companies should consider establishing frameworks for evaluating the human rights implications of new AI tools, to ensure potential human rights risks are considered early in the product design stage. Post-implementation testing and monitoring of AI should also occur, to identify trends and potential issues which may be emerging in AI use despite best intentions at the design stage.

- Expect greater transparency and explainability requirements. AI designers should also anticipate the introduction of requirements for companies to disclose explanations for AI decisions, for example, in court or regulatory proceedings.

- Be prepared for regulation of emerging technologies. Companies should anticipate that future regulations will target the outcomes produced by technology, so will also extend to new and emerging technologies, including those in testing and development.

Increased disclosure requirements and regulatory scrutiny.

- Anticipate increased regulatory scrutiny. Companies should be preparing for increased regulatory scrutiny of AI in the form of monitoring and investigations, by both existing regulators and the proposed new AI Safety Commissioner.

- Invest in systems and processes for new procedural rights and disclosure requirements. Companies should also plan for and invest in systems to address likely increased customer-facing processes and disclosure obligations regarding AI decisions – specifically, notifications to individuals when AI is materially used to make decisions that affect their legal or similarly significant rights, and a process for effective human review of AI decisions (by someone with the appropriate authority, skills and information), to correct any errors that have arisen through using AI.

BACKGROUND

On 27 May 2021, the Australian Human Rights Commission (with major project partners Herbert Smith Freehills, DFAT, LexisNexis and UTS) published the Report, marking the end of a three year project on the human rights implications of new technology.

The Report’s 38 recommendations focus on two key areas:

- how AI can be used in decision making in a way that upholds human rights with a view to promoting fairness, equality and accountability; and

- how people with disability experience digital communication technologies[1].

This article focuses on implications for the private sector of the Commission’s recommendations concerning “AI-informed decision making”, meaning a decision or decision-making process, that is materially assisted by AI, which has a legal, or similarly significant, effect for an individual.[2] The Commission notes that human rights can be impacted by a decision (eg rejection of a bank loan to an individual based on their gender) or by a decision-making process (eg an algorithmic tool used to determine the risk of recidivism which includes race as a relevant weighted factor).[3]

This distinction is important to bear in mind since, although a decision made by an AI system may itself be lawful, being unable to produce an explanation for the decision could put decision makers at risk of non-compliance with obligations to disclose information in certain situations, including to a court or regulator.

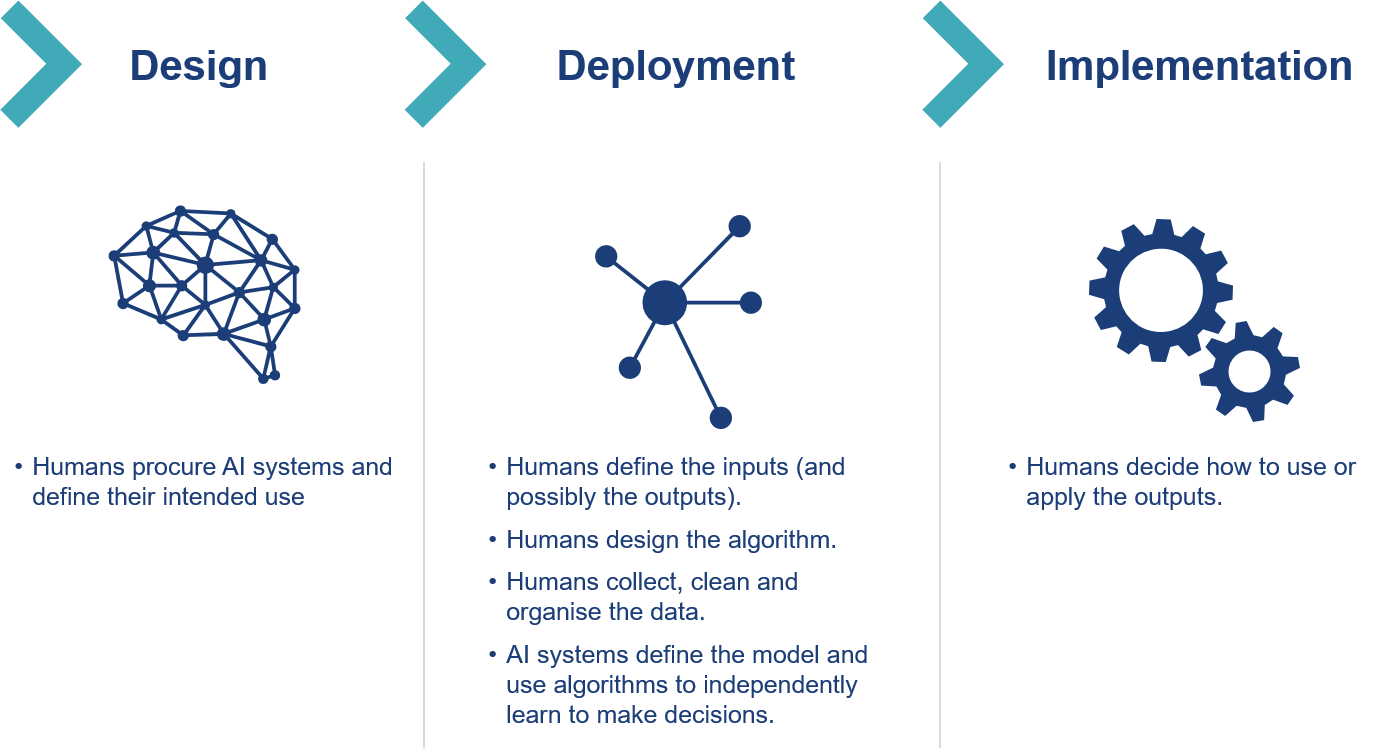

Figure 1: The lifecycle of designing and using an AI decision making system[4]

The Report also explores “algorithmic bias”, where an automated system produces unfair decisions. This can be caused by bias in the data or the design of the AI system itself, and may result in unlawful decisions being made if they discriminate against a person on the basis of a protected attribute such as race, age or gender.[5] Although the risk of discrimination in decision making is not new, it can be harder to detect when decisions are made by opaque or ‘black box’ AI systems that obscure the reasons for a decision.[6] There is also a risk that AI systems may use other information as a “proxy” for a protected attribute to produce decisions that result in indirect discrimination.[7] For example, if a group of people belonging to the same ethnic group reside in the same suburb, an individual’s postcode may become a proxy for their ethnic origin.[8]

SPECIFIC RECOMMENDATIONS

TECHNOLOGY OR OUTCOME DEPENDENT REGULATION?

The Commission recommends that Australia’s regulatory priorities should be guided by three key principles: first, regulation should protect human rights; second, the law should be clear and enforceable; and third, co-regulation and self-regulation should support human rights compliant, ethical decision making. The Report notes that different regulatory approaches may be taken in relation to new and emerging technologies, however:

[a]s a general rule, the regulation should target the outcome of the use of that technology. Few types of technology require regulation targeted specifically at the technology itself.[9]

Consistent with this approach (which is likely also driven by pragmatic considerations, given the swift rate of technological change), the Commission does not propose a statutory definition of AI-informed decision making. Nevertheless, it has recommended targeted reform in high-risk areas, including a moratorium on the use of facial recognition technology in areas such as law enforcement until adequate human rights protections have been enacted.[10] As we have previously argued, we do need to ensure that such reforms do not stifle innovation.

The Commission also recommends enacting a statutory cause of action for serious invasion of privacy,[11] echoing recent recommendations from law reform commissions and regulators.[12] Our discussion of the Federal Government’s response to similar issues raised by the ACCC’s Digital Platform Inquiry, and impacts for Australian privacy law, is available here.

The Commission has also called for the establishment of an AI Safety Commissioner to build the capacity of regulators to address issues around and investigate the development and use of AI, including identifying and mitigating human rights impacts.[13]

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRIVATE SECTOR

In relation to AI-informed decision making, the Report highlights potential areas of law reform to ensure decision making is “lawful, transparent, explainable, used responsibly, and subject to human oversight, review and intervention”.[14]

Different accountability considerations will apply to AI-informed decision making in the private sector compared to the public sector (as the public sector must observe administrative law requirements).[15] There are, however, specific situations where the law imposes obligations in respect of private sector decision making, which must be met irrespective of how the relevant decision is made. For example, the Report notes that company directors must exercise their powers and duties, including when making decisions, with care and diligence. Any use of AI in this context may come under scrutiny if that use fails to satisfy directors’ obligations.[16]

Some of the specific recommendations relating to private sector use of AI include introducing laws which would:

- require companies to notify affected individuals when AI is used in decision making processes that affect individuals’ legal, or similarly significant, rights;[17]

- provide a rebuttable presumption that entities are legally liable for decisions regardless of whether they are automated or made using AI;[18] and

- allow a court or regulatory body to draw an adverse inference about a decision-making process where a company fails to comply with orders for the production of information, even if the decision maker used technology such as AI which would make compliance difficult.[19]

The Report also recommends that:

- guidance should be issued to the private sector on undertaking human rights impact assessments in developing AI-informed decision making systems; and[20]

- companies should give individuals a practical way to appeal decisions to a body that can review AI-informed decisions,[21] noting however that the Commission does not presently recommend that companies “be legally required to make provision for human review” in circumstances where the private sector is not subject to the administrative law principles which govern government decision making.

The Report’s recommendations will be particularly relevant to private sector companies subject to existing legal obligations in relation to decision-making. For example, the requirement on financial services licensees to act “efficiently, honestly and fairly”[22] in the provision of financial services has been held to “connote a requirement of competence” and “sound ethical values and judgment in matters relevant to a client’s affairs”.[23] In making decisions regarding the products and services they offer to customers, financial service licensees should consider the accuracy of using AI compared with conventional methods, and only proceed when sufficiently confident that they can comply with their obligations.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR GOVERNMENT

The Report also outlines recommendations for public sector AI use. Beyond what is proposed in the private sector context, the Commission also recommends introducing legislation that would:

- prohibit the use of AI in making administrative decisions if the decision maker cannot generate reasons or a technical explanation for an affected person;[24]

- create a right to merits review for any AI-informed administrative decision;[25] and

- mandate the use of human rights impact assessments before using AI-informed decision-making systems to make administrative decisions by or on behalf of government.[26]

RECENT EU DEVELOPMENTS: A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

The Report does not recommend any prohibition on AI-informed decisions but focuses instead on their transparency and explainability. This is a different approach to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, which currently prevents individuals (with some exceptions) from being subjected to a decision “based solely on automated processing” where that decision produces a legal or similarly significant effect. The Report’s discussion of “high risk” AI systems, without proposing specific laws to address these matters, also raises similar issues to those contemplated in the EU Commission’s recent regulatory proposal. That involves introducing obligations for pre-product launch testing, risk management and human oversight of high risk AI), with maximum penalties of EUR 30 million or 6% of total worldwide annual turnover for non-compliance.

[1] Australian Human Rights Commission, Human Rights and Technology (Final Report, 2021) 9 (Report) 9.

[2] Ibid 38.

[3] Ibid 38.

[4] This infographic is based on a figure in the Report: see ibid 39.

[5] Ibid 106.

[6] Ibid 63.

[7] Ibid 106.

[8] Ibid 106.

[9] Ibid 26.

[10] Ibid 116, Recommendations 19 and 20.

[11] Ibid 121, Recommendation 21.

[12] Victorian Law Reform Commission, Surveillance in Public Places (Final Report, 1 June 2010); NSW Law Reform Commission, Invasion of Privacy (Report 120, April 2009); Australian Law Reform Commission,

Serious Invasions of Privacy in the Digital Era (Report 123, September 2014); ACCC, Digital Platforms Inquiry (Final Report, June 2019).

[13] Report (n 1) 128, Recommendation 22, and 132.

[14] Ibid 8, 13.

[15] Ibid 13.

[16] Ibid 76. See, eg, Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 180.

[17] Ibid 194, Recommendation 10.

[18] Ibid 194, Recommendation 11.

[19] Ibid 195, Recommendation 13.

[20] Ibid 75, Recommendation 9.

[21] Ibid 12.

[22] Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 912A(1)(a). Herbert Smith Freehills has prepared a note on this obligation, titled “Regulatory “Rinkles”: Efficiently, honestly and fairly (Part 2)”, which is accessible here.

[23] Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AGM Markets Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 3) [2020] FCA 208 at [505].

[24] Report (n 1) 194, Recommendation 5.

[25] Ibid 194, Recommendation 8.

[26] Ibid 55, Recommendation 2.

Key contacts

Disclaimer

The articles published on this website, current at the dates of publication set out above, are for reference purposes only. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action.