Stay in the know

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs

This is consistent with our professional experience and reflects the escalation and rising complexity of the threat landscape. In July 2024, we spoke with Abigail Bradshaw, Head of the Australian Cyber Security Centre.1 She described a recent proliferation in activity by both criminal (that is, financially-motivated) actors and state-based actors, with a blurring of the lines between the two types.

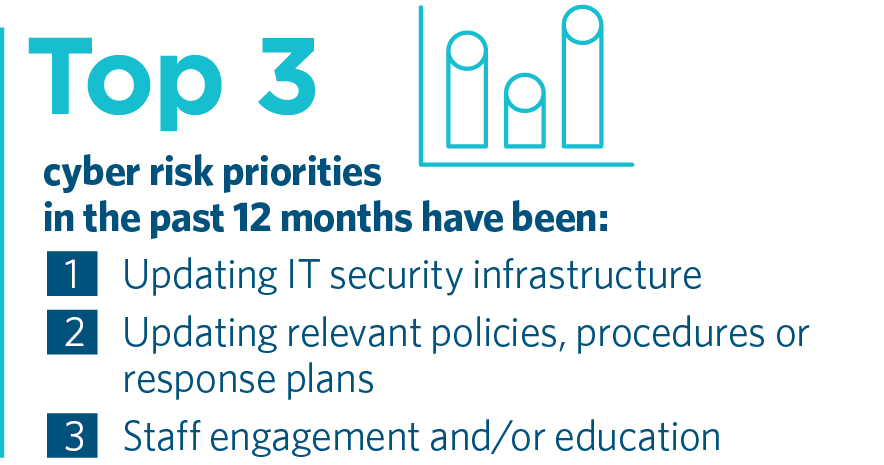

Surveyed organisations also vary in their approach to prioritising cyber risk mitigation strategies. In the main, they are focused on updating their IT infrastructure, IT policies, procedures and incident response plans, as well as staff education. These strategies sit squarely within the wheelhouse of an organisation’s IT security function, which may explain why 79% of survey respondents continue to see cyber risk as owned by their Chief Information Officer (CIO) or Chief Information Security Officer (CISO). There is little doubt that the IT team and associated experts play a critical role in building cyber resilience and responding to cyber incidents. However, a mindset that puts IT at the centre can put an organisation at risk of falling short on the enterprise-wide preparation required to meet cyber threats. This includes building the confidence of its board, testing its incident responders and upskilling the legal team.

In saying this, we understand why managing cyber risk often falls to the CIO or CISO. In our experience, many incidents could have been prevented with basic IT hygiene, such as keeping software updated by promptly rolling out patches, deploying enterprise-wide multi-factor authentication systems, restricting and regularly reviewing privileges and putting your remote desktop protocol behind the organisation's firewall.

Like our survey respondents, we also believe cyber security is, at its core, an IT risk. But cyber risk is also no different to any other risk. Boards, executives and legal leaders need to understand cyber risk so they can fully participate in discussions about it and to meaningfully respond to threats.

One of the most acute challenges to the effectiveness of organisations' responses to cyber risk is language: technical teams and boards are still struggling to understand each other. “There is a language disconnect,” says Herbert Smith Freehills Partner and APAC Cyber Security Head Cameron Whittfield. “CISOs give briefings, and boards ask questions, but it is not clear to us whether ultimately there is shared understanding, and often we play the role of translator.”

Rising regulatory focusRegulatory scrutiny in Australia is only increasing as a multitude of regulators take action on cyber. And while upcoming law reform may provide the guidance that businesses crave, it will also increase the regulatory burden and associated legal risks.

|

Simulations give participants a risk-free opportunity to clarify roles and responsibilities and to practice delegations and decision-making. They also shine a light on weaknesses in an organisation’s cyber resilience program. This leads to a renewed focus and investment in systems and processes, in advance of a real-life crisis.

And yet too many organisations are still only turning their attention to cyber preparedness when an attack occurs.

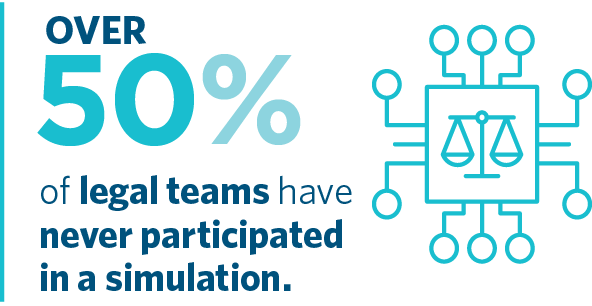

This is particularly the case with boards. This year’s survey shows that 70% of boards have been educated about cyber risk, but only 40% have participated in a simulation exercise. Participation in simulations was notably higher for executive teams, at 69%.

The appropriate delineation of roles and responsibilities between the board and the executive team in a cyber crisis can be markedly different from everyday operations – particularly for ‘active’ boards.

“It can come as a surprise to directors that they play a relatively limited role in responding to a cyber crisis. While they must proactively supervise the response, very few decisions bubble up to board level. Boards must have confidence in management’s ability to respond, and the interplay between management and the board is critical,” Whittfield says. Ironing out creases in a simulated environment facilitates a smoother response in a real crisis.

Indeed, in our practice, we observe that sophisticated boards often bring a welcome sense of calm and strategic clarity to cyber incident response.

It is perhaps not surprising that boards have been reviewing their skill matrices and expending energy seeking new directors with cyber expertise or experience. Notably, 35% of organisations have done so. But there is a risk that complacency can stem from appointing a dedicated or uniquely qualified individual. “Effective incident response is multi-disciplinary,” Whittfield says. “Relying on an individual or taking comfort in a particular individual’s expertise can lead to a false sense of security. Cyber is like any area of business risk, and all directors should be armed with the skills to interrogate and actively participate in discussions. It is also entirely appropriate for a board to have the ability to directly interrogate cyber experts brought in to assist the organisation.”

Cameron Whittfield

Partner - APAC Cyber Security Head

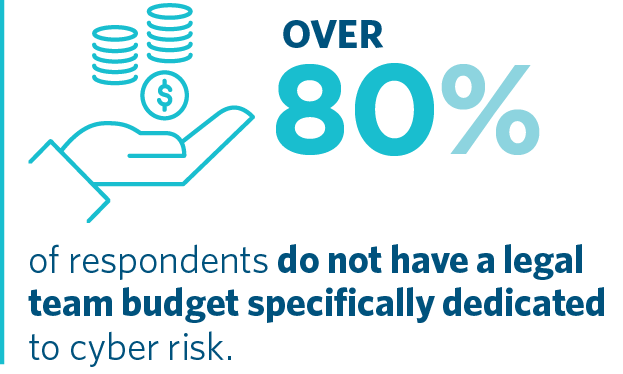

“These investment decisions echo the intense resourcing pressures imposed on in-house legal teams in the current environment. However, they do not sit comfortably alongside the integral role played by legal advisers in a cyber crisis,” says Senior Associate, Heather Kelly, who brings expertise in both corporate law and at the frontline of cyber incident management, as an in-house lawyer. This observation is not lost on many survey respondents: 75% of respondents regard the legal team as “central” to their organisation’s crisis response in the event of a cyber incident.

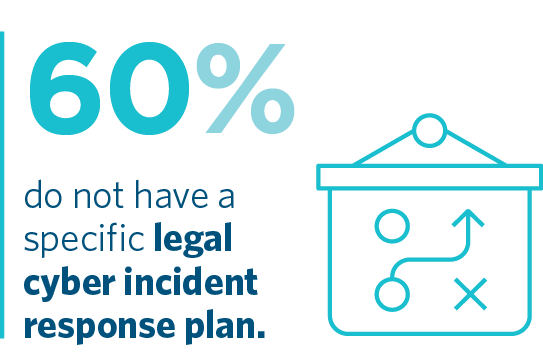

Lawyers may be intimately involved in reviewing compromised data, engaging with regulators; drafting communications for staff, customers and suppliers; assessing compliance risk and operational impacts; responding to contractual claims; and engaging with insurers. “Missteps managing the legal side of each incident response workstream can have significant regulatory and commercial consequences,” says Kelly.

Heather Kelly

Senior Associate and Cyber Risk Advisory Lead

Christine Wong, a disputes partner with expertise in contentious privacy and data disputes, also raises the role of lawyers in managing legal professional privilege. In Wong’s view, “privilege should not get in the way of an effective response, but given the real risks of follow-on litigation, whether and how privilege applies should be considered in incident planning ahead of time and modified as needed when a live issue arises”.

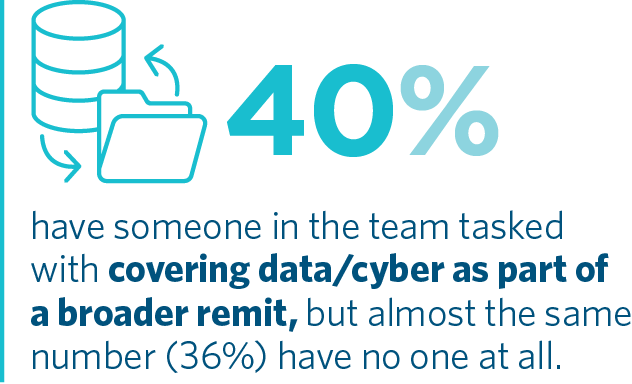

Lack of expertise is an aspect of cyber risk giving rise to great concern among survey respondents. Only 14% of organisations have a resource in their legal team dedicated to or specialising in cyber and data. In our view, this concern is somewhat misplaced. It may sound comforting and indeed prove useful having such an individual available day-to-day. But engaging a trusted external adviser may support a more efficient and effective incident response, particularly where their expertise comes from deep experience across a broad range of incidents and industries.

The use of a preferred, trusted adviser needs to be managed in the context of any insurance policies. 76% of respondents have cyber insurance that often refers the policyholder to a list of the insurer’s panel advisors. However, 80% say they would not engage a law firm from their insurer’s panel.

Our survey data indicates this position arises, in part, due to a conflict of interest (perceived or real) between the policyholder and insurer on the extent of coverage or the management of any incident response. Our clients often express concerns about this issue and query whether cyber insurance panel law firms are acting in their best interests. While this may be confronting, it is a conversation unfolding regularly in boardrooms, as directors look to ensure they have the right type of support.

Senior Associate Laura Newton brings deep expertise in regulatory and incident response across the public and private sectors. She believes that “it is imperative that businesses understand, practically, what a conflict of interest in the insurance panel model might mean for them – for example, understanding if the panel firm also advises their insurer on coverage determinations, and what information the panel law firm will share with the insurer, including any legal advice”.

Obtaining adviser pre-clearance from insurers, in advance of an incident, puts an organisation in a strong position to be supported before, during and after an event, by a team that understands their people, processes and business strategy. The fly-in-fly-out cyber triage approach is certainly losing favour with large corporates.

Laura Newton

Senior Associate

The contents of this publication are for reference purposes only and may not be current as at the date of accessing this publication. They do not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Specific legal advice about your specific circumstances should always be sought separately before taking any action based on this publication.

© Herbert Smith Freehills 2024

We’ll send you the latest insights and briefings tailored to your needs